The COVID pandemic has taught us that we shouldn't ignore warnings about dire health threats. And scientists have been warning about the dangers of antimicrobial resistance, or AMR, for decades. In 2019 the World Health Organization declared AMR one of the top 10 global public health threats to humanity, and the United Nations estimated it could kill as many as 10 million people a year by 2050. We are already seeing high numbers of such deaths: drug-resistant infections killed nearly five million people in 2019.

AMR means the treatments we use to fight bacteria, viruses, fungi and other pathogens no longer work. Resistance evolves naturally over time, but the overuse and misuse of antimicrobial drugs in medicine and agriculture are speeding it up.

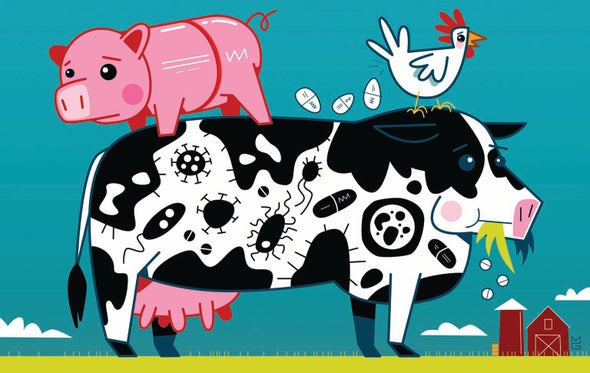

Fixing this problem will require a focus on human, animal and environmental health. The food animal industry is one of the chief users of antibiotics and one of the largest contributors to antimicrobial resistance. Governments need to better regulate livestock farmers' use of these drugs, and restaurants, supermarkets and consumers must demand antibiotic-free meats wherever they buy them.

About 70 percent of medically important antibiotics sold in the U.S. are for animals. Sometimes they are needed to treat illness, but for many years livestock and poultry farmers also gave healthy animals antibiotics to promote their growth. Although it is no longer legal to administer antibiotics for that purpose, farmers still give them to “prevent” infections, despite little evidence that this works.

Modern factory farms are the ideal breeding grounds for antibiotic-resistant infections: many animals are raised in crowded, unsanitary conditions. Add to that the fact that the antibiotics are given at low doses that can kill off weak pathogens while inadvertently selecting out the strongest ones, and you've got the “perfect storm” to create bacterial resistance, says Gail Hansen, a consultant on public health policy and antibiotic resistance.

The chicken industry has made some progress in reducing antibiotic use over the past 10 to 15 years—mainly thanks to consumer pressure, according to Hansen. Farmers stopped injecting chicken eggs with antibiotics to prevent new chicks from catching an infection from microbes on the egg. Instead they now wash eggs.

These changes are an improvement, but chickens receive only a small fraction of the total amount of antibiotics used in food animals. Cattle and pig farming collectively account for about 80 percent. Reducing their antibiotic use will require more significant changes to their diets and living conditions. But given the importance of these drugs, we need to pressure livestock farmers to make those changes.

Farmers are not the only ones who should be taking responsibility. Food retailers have a lot of power, too. In 2018 McDonald's pledged to set reduction targets for the amount of medically important antibiotics in its beef by the end of 2020, but it did not do so until late 2022. A recent investigation by the Bureau of Investigative Journalism and the Guardian found that companies supplying beef to McDonald's, Taco Bell and Walmart are still getting meat from farms using antibiotics classified by the WHO as “highest priority critically important” to human health.

Medical settings such as hospitals have created stewardship committees that evaluate whether a given use of antimicrobials is appropriate. The U.S. should create similar programs in the food animal industry. Ideally it would also set target limits for antimicrobial use, as European countries have done. The Netherlands, for example, set a policy that decreased the use of antibiotics in animals by 50 percent within three years. The U.S. government should do something similar but can't: no federal agency—not the FDA, not the U.S. Department of Agriculture—has the power to set limits on the amount of antibiotics used or offer incentives to reduce their use. Any efforts by Congress to give an agency these powers are likely to be fiercely fought by agricultural lobbyists, but it's worth trying.

Antibiotic use in agriculture is just one factor contributing to the rise of antimicrobial resistance. The human health-care system, including doctors and pharmacies that distribute the drugs, can also follow best practices to help antibiotics stay useful longer. If we can't stop resistance from occurring, we can at least slow it down until researchers and pharmaceutical companies can develop new infection-targeting drugs. After all, our lives depend on it.