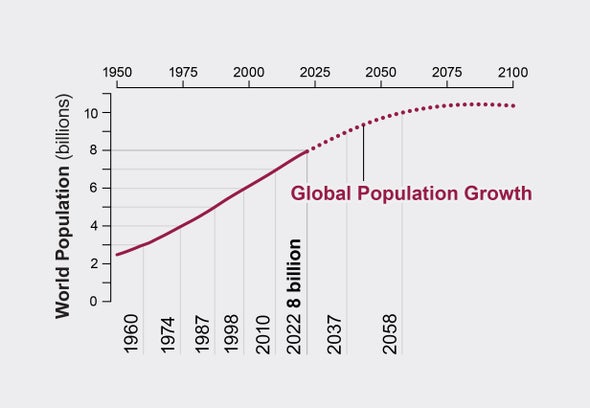

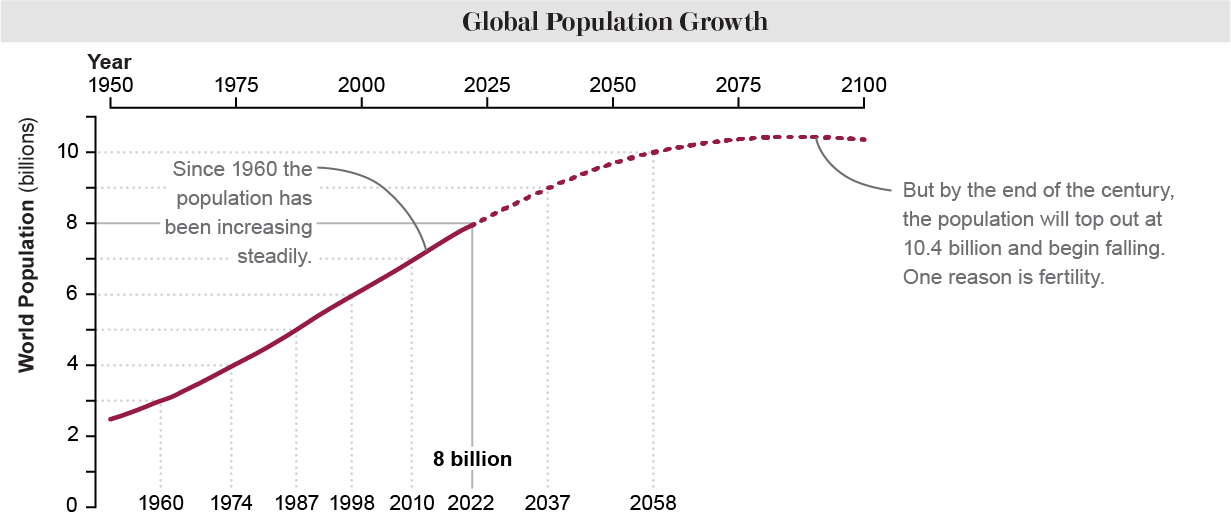

On November 15, 2022—as estimated by demographers—the count of humans on this planet reached eight billion. Population growth has been steady over the past few decades, with billion-person marks coming every dozen years or so. But that pattern is changing. Growth is beginning to slow, and experts predict the world's population will top out sometime in the 2080s at about 10.4 billion.

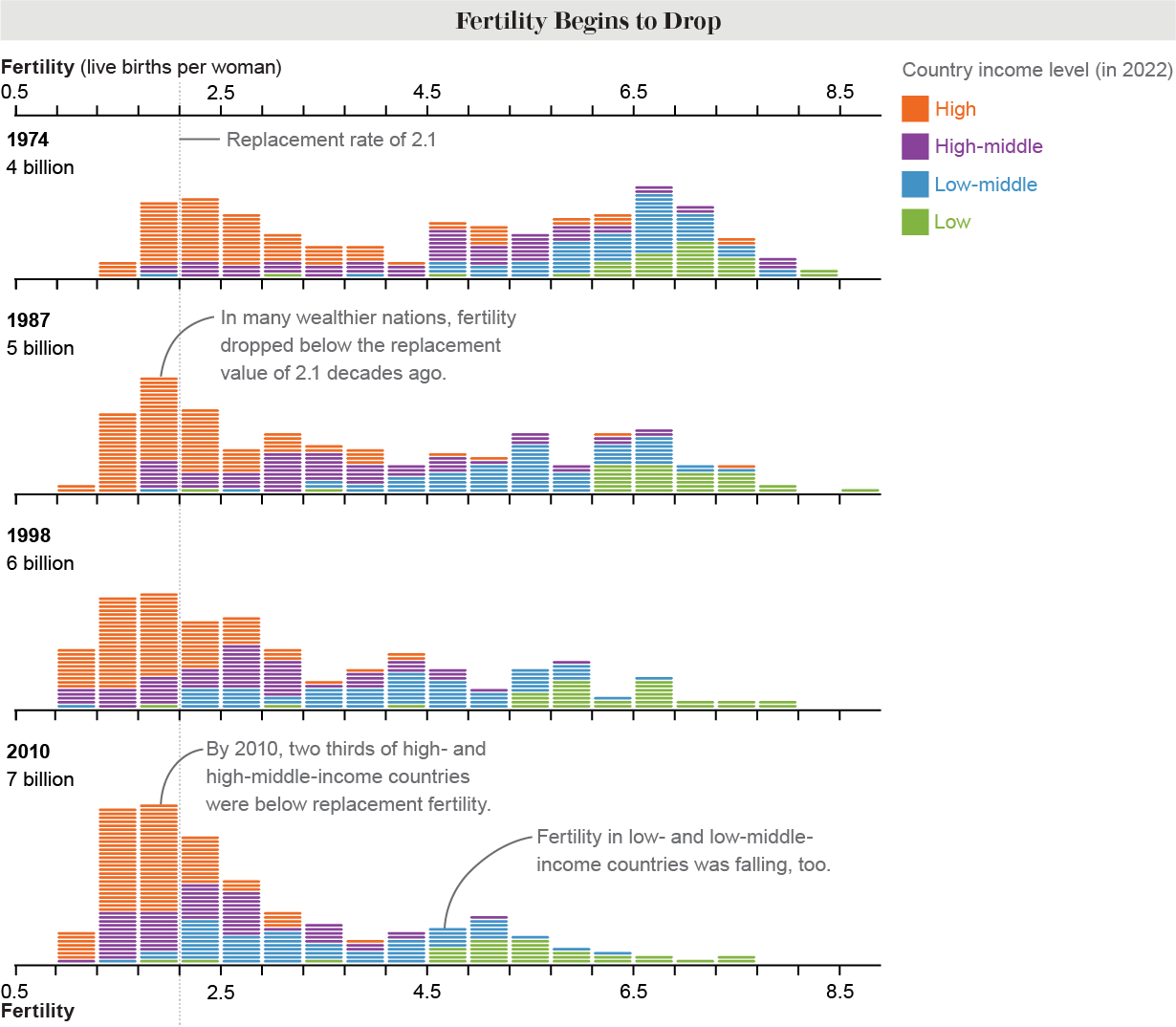

That slowdown is partly the result of a shift toward fewer offspring—a phenomenon that is happening almost everywhere around the world, though at different rates. High-income nations now have the lowest birth rates, and the lowest-income nations currently have the highest birth rates. “The gap has continued to widen between wealthy nations and poorer ones,” says Jennifer Sciubba, a social scientist at the Wilson Center in Washington, D.C., who has written about these planetary-scale demographic shifts. “But longer term,” she says, “we're moving toward convergence.” In other words, this disparity among nations' birth rates isn't a permanent chasm. It's a temporary divide that will narrow over the coming decades.

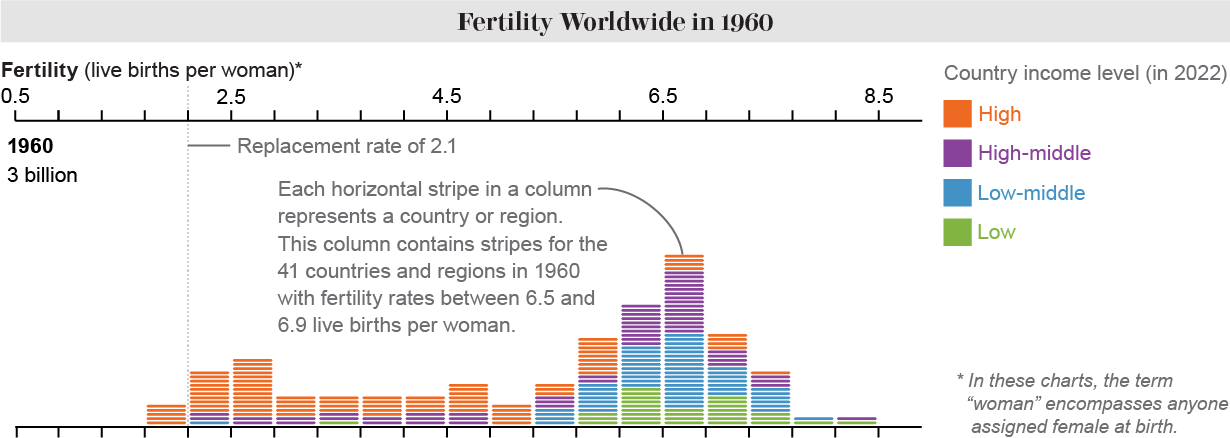

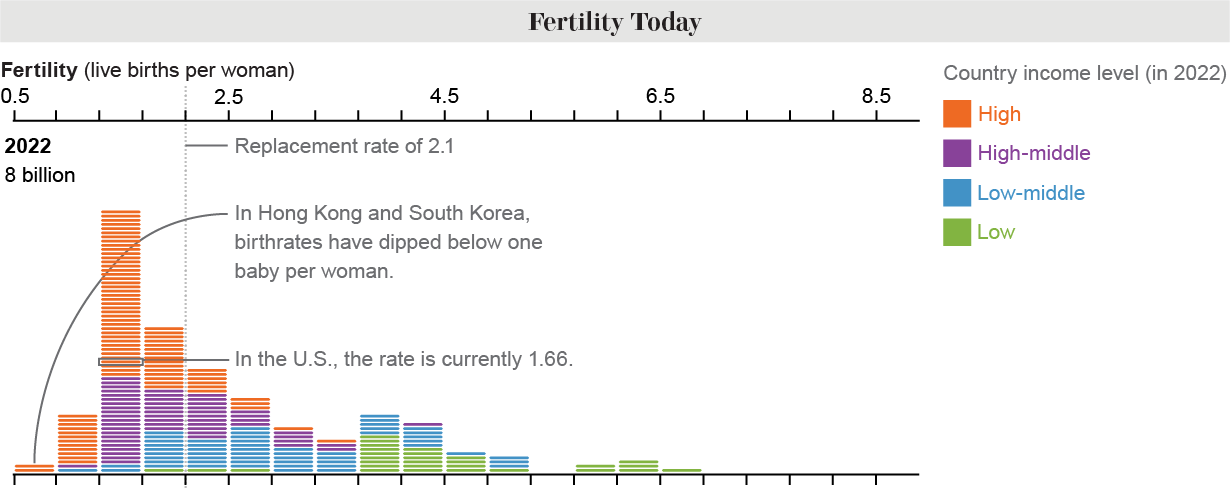

Many factors contribute to the waxing and waning of the world's population, such as migration, mortality, longevity and other major demographic metrics. Focusing on fertility, however, helps to illuminate why the total number of humans on Earth seems set to fall. Demographers define fertility as the average total number of live births per female individual in a region or country. (In the accompanying graphics, the term “woman” is used to encompass anyone assigned female at birth.) The U.S.'s present fertility rate, for example, is about 1.7; China's is 1.2. Demographers consider a fertility rate of 2.1 to be the replacement rate—that is, the required number of offspring, on average, for a population to hold steady. Today birth rates in the wealthiest countries are below the replacement rate. About 50 percent of all nations fall below the replacement rate, and in 2022 the region with the lowest fertility rate (0.8) was Hong Kong. Over the coming decades most of the rest of the world's countries will likely follow suit. Here's how that might look.

In 1960, when the world's population was three billion, nearly every country had a fertility rate above 2.1 live births per woman.

But over the subsequent decades that began to change. A country's fertility rate tends to be correlated with its average income. Wealthier countries were the first to move toward fewer offspring, but lower-income countries are also following the same trend.

Here's the picture today, as we crest eight billion.

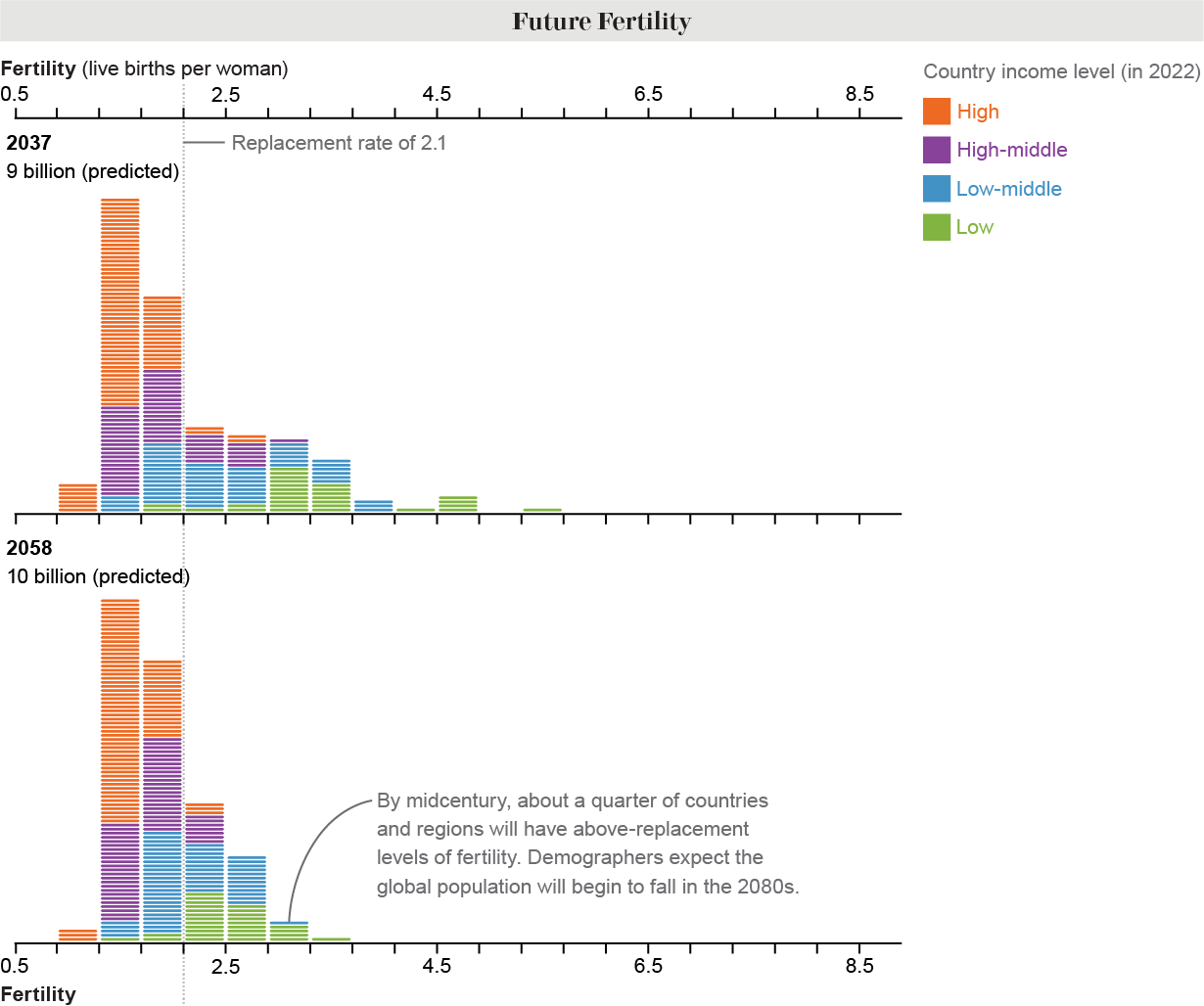

Fertility was especially disparate in higher- and lower-income countries from the 1990s through today. But by the end of this century fertility rates worldwide will reconverge at a lower number.

These numbers provide insight into how—and where—the population growth rate is changing. But humanity's future clearly depends on many things besides fertility. For example, people in wealthier nations may produce fewer children, but those offspring tend to consume more resources—so rich countries can still have outsize planetary impacts despite their dwindling populations. Organizations such as the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs—which tracks and predicts human population numbers—are working toward policy-based solutions for how all of us can have healthy, satisfying and sustainable lives on Earth. A clear-eyed understanding of population shifts is critical for reaching that bright future.