Last Friday the Supreme Court issued a stay on a lower court ruling that revoked the Food and Drug Administration’s more than 20-year-old approval of mifepristone, one of two medications that have been prescribed together for decades in the U.S. to end unwanted pregnancies. The ruling temporarily preserves access to a safe and effective abortion medication while the case goes through appeals.

Two weeks earlier Texas district judge Matthew Kacsmaryk had ruled in favor of the Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine, a group of antiabortion organizations and doctors demanding the withdrawal of mifepristone’s FDA approval. The Department of Justice and the drug’s manufacturer, Danco Laboratories, quickly appealed the decision. About a week later the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals only partially stayed the ruling, maintaining mifepristone’s approval but restricting its distribution by mail. The Supreme Court decision removes that limit for now.

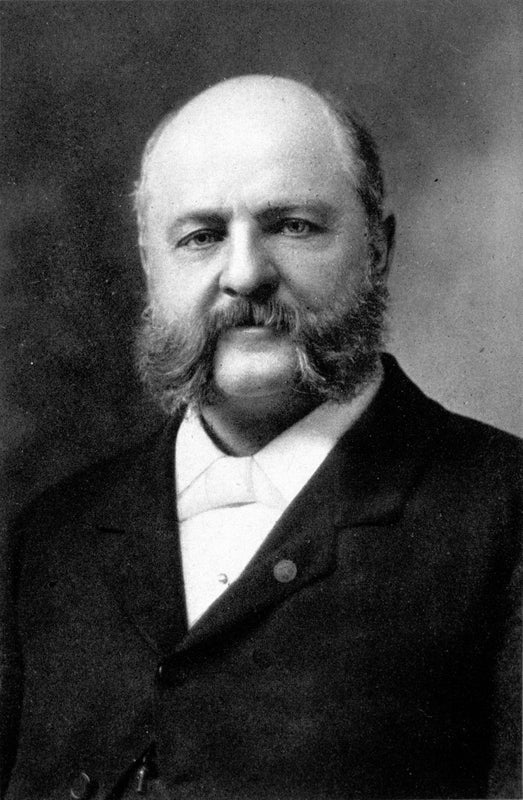

Kacsmaryk’s initial ruling and the Fifth Circuit decision cited a 19th-century law known as the Comstock Act of 1873, which made it illegal to send “obscene, lewd or lascivious” materials by mail—including not just nude drawings but also materials or information related to abortion or contraception. That law was spearheaded by Anthony Comstock, a Christian moralist activist and head of the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice. Congress passed the law and appointed Comstock as a special agent of the U.S. Postal Service, giving him the power to arrest people for violations. Comstock ultimately became a public laughingstock for his prudishness, and the Supreme Court overturned the law’s restrictions on birth control in 1965. But the rest of the Comstock Act quietly remained on the books—and the lawsuit over mifepristone is likely to put Comstock’s antiabortion policies back on the Supreme Court’s docket.

Science journalist and author Annalee Newitz spent years researching and interviewing people about the Comstock Act and Comstock himself for their 2019 novel The Future of Another Timeline, in which characters time travel to try to prevent Comstock from getting his law passed. Scientific American spoke with Newitz about what history their research uncovered and how a 150-year-old obscenity law is being used to restrict abortion and reproductive rights in the 21st century.

[An edited transcript of the interview follows.]

Who was Anthony Comstock, and how did the Comstock Act come about?

Anthony Comstock was a very famous moral crusader based in New York [City] in the mid-19th century. His career started mostly because he was interested in stamping out obscenity—and by obscenity he meant any imagery [or literature] that contained nudity. He was extreme for his time, but at a certain point, he managed to connect with the New York City YMCA, which was also against what they were referring to as “obscenity.” By connecting with them, he got access to a lot of powerful New Yorkers who were able to fund his campaign. He got himself a position as a special inspector at the postal service. Much of the Comstock Act’s power comes from the ability to regulate communications across state lines.

The law forbids the sending of obscene materials through the mail. Comstock was enforcing the law by ordering thousands of items through the mail, from contraceptives and sex toys to erotic images and abortifacients [substances that end a pregnancy]. Then, after receiving the items, he would prosecute the people sending them. He was targeting people who were known to be selling the raw material but also, more importantly, people who were selling any kind of information that was education-related, not obscene—literally things like “Here’s how to make a baby” and also information about birth control and abortion. The Comstock Act was actually a First Amendment exemption law. It was a law about obscenity: what could be said and what could be passed through the mail. Under that, any information or material related to reproductive health or abortion or sex education was classified as obscene.

That is a very different model from how, in the contemporary world, we understand abortion—because abortion was kind of precariously made semi-legal in the 1970s under the Fourth Amendment, under privacy laws. So basically, to the extent that we started bringing the Comstock laws [a set of laws including and related to the Comstock Act] back, they do a complete end-run around any of the laws that we’ve made since that time to protect people’s ability to have abortions—because it’s not about privacy; it’s about obscenity.

In the early 20th century there was a meme that was started by the playwright George Bernard Shaw, who wrote an op-ed in the New York Times making fun of Comstock—because by the late 19th century, even though the laws were in effect, many modern young people thought that he was an idiot. These included people reading presidential candidate Victoria Woodhull's popular newspaper, Woodhull & Claflin's Weekly, which Comstock continually tried to shut down. George Bernard Shaw said America was suffering from “Comstockery.” He was using this term to refer to the censorship and puritanical nature of American art, and it became a meme. People started using ‘Comstockery’ to make fun of any kind of art or storytelling or writing or politics that was old-fashioned and puritanical.

How have the Comstock Act and related laws evolved over time?

The Comstock laws were being actively used basically up through the 1960s, which is shocking. And in the 1970s we see on the Supreme Court a revolution in our understanding of what obscenity is and a kind of rejiggering of the First Amendment—because, remember, obscenity is an exemption to the First Amendment. In the early 20th century, this idea of Comstockery becomes really popular. The laws are viewed as old-fashioned. And they’re not really taken off the books, but they’re mostly ignored. And at the same time, courts are using them to continue limiting, especially, abortifacients, abortion information and reproductive health information.

In the 1930s there were some rulings around the Comstock Act that broadened its application to different kinds of birth control but at the same time limited how the law could be used if people were sending abortifacients for unlawful uses. So in the 1930s there’s this limit where it only counts under the Comstock Act if you deliberately are sending somebody something [to illegally abort a pregnancy]. Then, in the 1950s, there’s an expansion of the Comstock Act to include any substance that could lead to an abortion.

Then you get this shift in the early 1970s around privacy law, and reproductive health is placed under privacy. Pretty much every lawyer I’ve ever talked to about this who’s super knowledgeable about reproductive rights is like, Why did we do that? That was such a precarious ruling—so easy to roll back, as we’ve seen [with last year’s Supreme Court decision overturning Roe v. Wade]. But it seemed like a good idea at the time. But in the process, of course, that meant that these Comstock laws remained on the books in a lot of places.

In The Future of Another Timeline, characters travel back in time to try to prevent the Comstock laws. When you wrote the book, did you expect these laws would be used in a ruling like the recent mifepristone case?

Definitely not. I’m probably the only person who has written a time travel story about trying to defeat Comstock, although I’d love to be wrong about that. But there are a lot of folks who are law experts and obscenity experts, whose work I read over the years, who have said the laws that protect people’s rights to have an abortion and people’s rights to have access to birth control are super precarious—and what we really need to do is have a law that says abortion is legal and birth control is legal. But what we keep doing because of our Comstockery as a nation is saying, “Oh, we wouldn’t want to give people rights to have an abortion. Why don’t we just say that they have a right to do whatever they want in private, and then we’ll just avoid talking about the issue?” And what that means is that we continue to allow women to become second-class citizens whenever the fuck we want.

How did Comstock use the courts and other means to enforce his agenda?

In the 19th century, Comstock was like, I'm going to use ... surveillance, and I’ll use this brand-new position in the postal service [to police what he called obscenity]. He also had kind of an army of deputized suppressors of vice—he ran this organization called the New York Society for Suppression of Vice, which just sounds like something out of a Marvel comic. And they would do these arrests all the time. So it feels very much like, yes, it comes out of using the courts. But it also comes out of abusing police power because these were people who were, like, pseudo police officers, and they would figure out who was an abortion provider. Comstock once reported breaking into the house of someone who was performing an abortion and dragging him and the patient to the police station to make a point. He described the woman as 'very sick' when she arrived at the police station, which made me imagine that she was literally bleeding on the floor.

It’s all tied up with a lot of the same issues that we’re grappling with nowadays: What kinds of books should we allow children to read? What should police powers be? What is the role of courts? But you know, it’s funny, because now that they’re picking on mifepristone, I think we’re going to get a really funny backlash from an unexpected source, perhaps—which is the pharmaceutical industry. That’ll be interesting to see play out because I think that the pharmaceutical industry sees that, “oh, we know where this is going.” Like, “This is going to go after our bottom line.” I could easily see a judge saying, “We shouldn’t be sending Viagra [by mail] because it’s not for reproduction.”

We might get a similar situation to what Comstock faced in the 19th century, when he was really trying to prevent abortions and sex education. But because he went after art that contained nudity, he ended up pissing off a lot of people who were very powerful, who thought he was suppressing free expression and innocent expressions of intellectual curiosity.

What happened to Comstock himself?

He was basically laughed out of his positions of power. By the time he died, he really was considered to be just a joke. Right after he dies is when Margaret Sanger starts founding her clinics, which eventually become Planned Parenthood. So even that aspect of his work is kind of crushed under the wheels of this new era of family planning.

Given that the Comstock laws are being used to go after the distribution of abortion medication, could they also be used to go after contraception?

Yeah, I mean, I think that’s exactly why drug companies are sitting up and taking notice and sending briefs. This is now an attack on science. So they’re using abortifacients as an excuse to attack a broad range of medical interventions. [Editor’s Note: Congress repealed the parts of the Comstock Act dealing with contraceptives in 1971.]

If you were going back in time to rewrite your book, how would you write the next chapter in this story?

When I was working on the book, I was thinking about how Comstock’s strategy has continued into the present. But a big part of my book is about strategies of resistance and hope and how, in fact, Comstock was defeated pretty soundly. Not only were his laws ignored [after a series of Supreme Court decisions strictly limiting their application], but also he was a laughingstock. The way that happened was that very different groups of people came together. In my book, I show that the wealthy elite of New York had common cause with these marginalized women who were at the Chicago World’s Fair performing belly dances. And this is all based on a true story: Comstock tried to shut down one of the exhibits in the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair because they were putting on belly dancers, and he thought belly dancing was obscene. These are not groups that normally hang out together, but they did come together.

I think that’s why now it’s really interesting to see the power players who are coming together [to oppose restrictions on abortion]. We are seeing people resisting in the name of feminism and in the name of queer rights…. But then you also have drug companies—super capitalists—coming together with these groups that normally they’re not hanging out with. I think we’re seeing the beginnings of a new kind of resistance that combines powerful capitalists and powerful politicians with marginalized people who are the victims of these Comstock laws. So I think there’s a lot of hope.