As the world hurtles toward a future with temperatures above the thresholds scientists say will lead to the worst climate disruptions, humanity needs to take all the actions it can—collectively and as individuals—to bring planet-warming emissions down as quickly as possible. Governments and companies need to do the lion’s share of the work, but ordinary people will also need to make changes in their everyday lives. A crucial question has been how best to spur people toward more climate-friendly behaviors, such as taking the bus instead of driving or reducing home energy use.

New research published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA pooled the results of 430 individual studies that examined environment-related behaviors such as recycling or choosing a mode of transportation—and that looked into changing those behaviors through several interventions, including financial incentives and educational campaigns. The authors analyzed how six different types of interventions compared with one another in their ability to influence real-world behavior and at how five behaviors compared in terms of how easy they were to change.

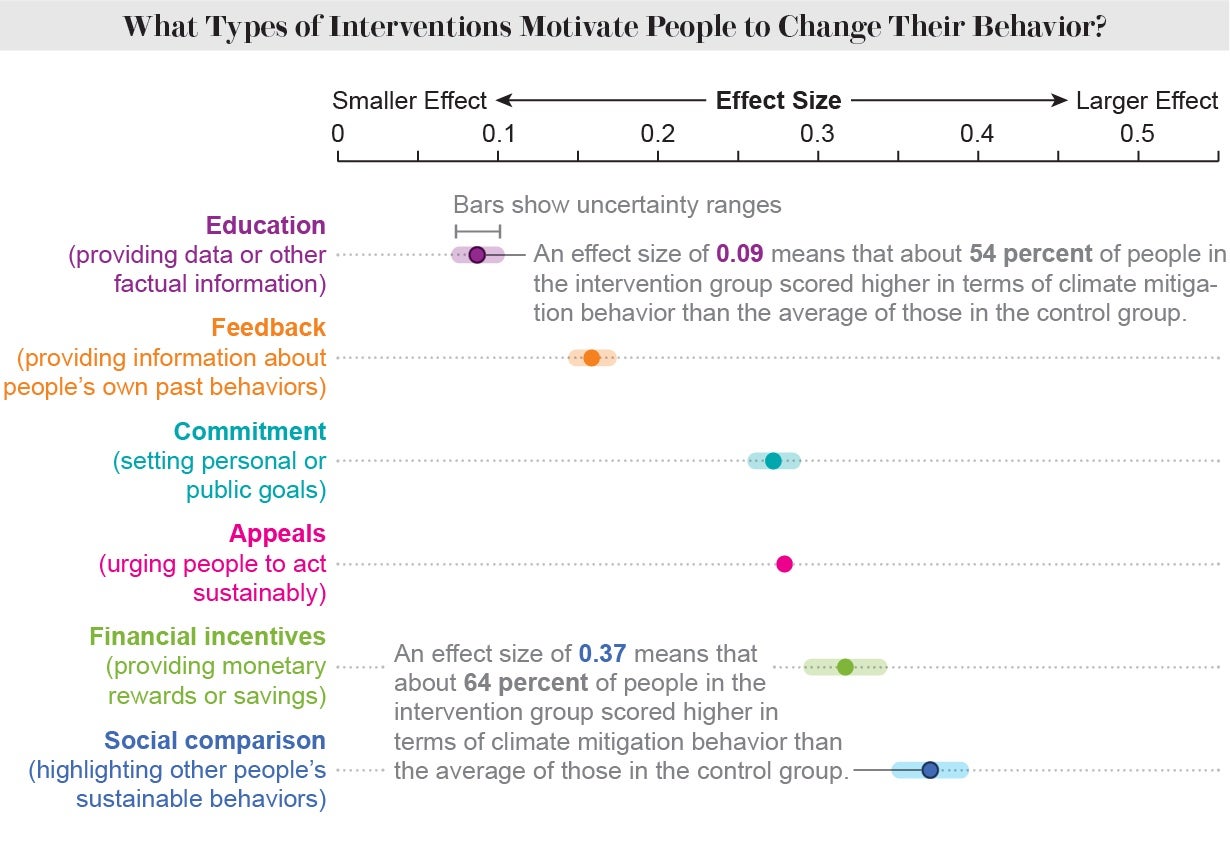

As can be seen in the graphic below, financial incentives and social pressure worked better at changing behaviors than did education or feedback (for example, reports of one’s own electricity use). The results reinforced what environmental psychologists have found when looking at these interventions in isolation.

Though education can be necessary to make the public aware of a problem in the first place, “we find over and over again that it’s not very effective” at actually changing behaviors, says study co-author Magnus Bergquist, a psychologist at the University of Gothenburg in Sweden. It’s similar to how knowing that we should exercise more or drink less alcohol doesn’t mean we will do so, he explains. “Just knowing what’s right, or healthy, or environmentally friendly isn’t really a sufficient model for changing behaviors,” Bergquist says.

On the flip side, the new research found social pressure had the strongest effect on behavioral change. Such pressure can take passive forms, such as the sight of a larger number of our neighbors adding solar panels to their houses or purchasing electric cars, or more active ones, such as home energy reports that compare our energy use with our neighbors’.

“People judge their own behavior against what others are doing. There’s a strong tendency to conform to social norms,” says Susan Joy Hassol, director of Climate Communication, a nonprofit science and outreach project. For example, “those who know someone who has stopped flying because of climate change are more likely to curtail their own flying—and the effect is increased if it’s a high-profile person that’s stopped flying,” adds Hassol, who was not involved with the new study. “This social contagion is why it’s so important to talk about the climate actions you take.”

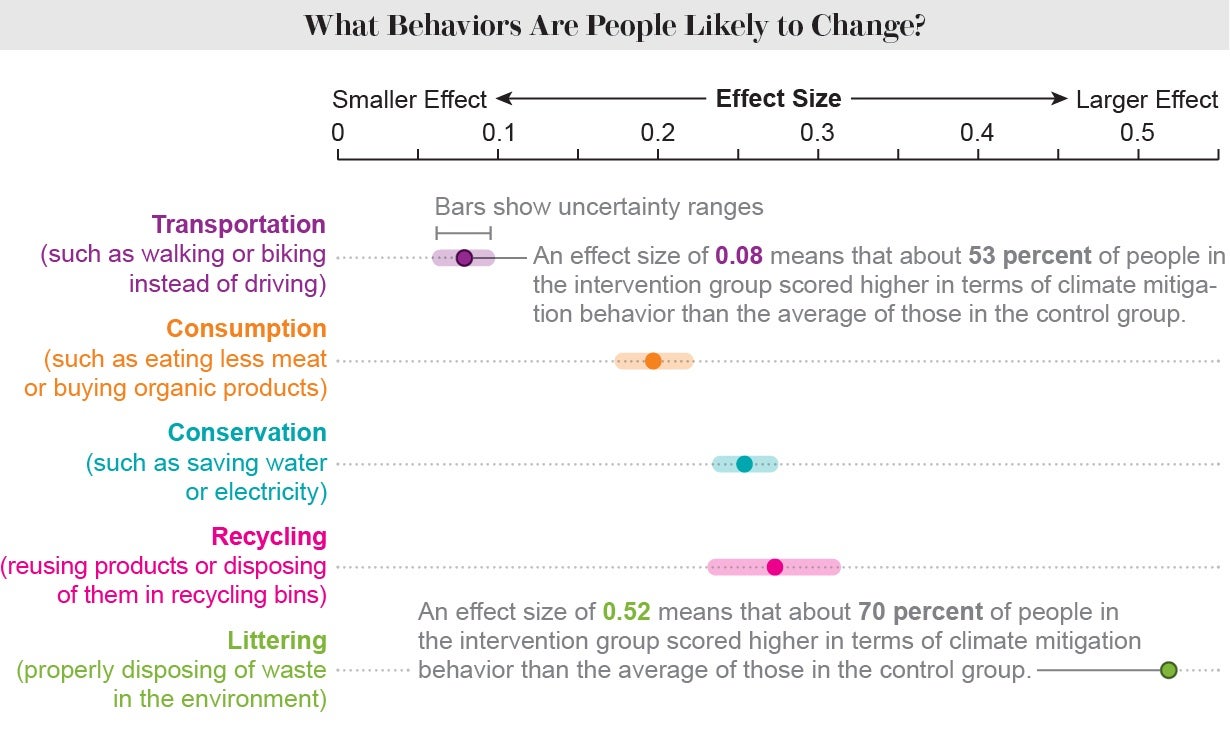

The study also found that some behaviors were easier to change than others, as seen in the graphic above. The behavior most likely to be changed was littering. Transportation was the least likely to be altered. But even a relatively small rise in the percentage of people who use more climate-friendly transportation can reduce emissions more than a larger shift in behaviors such as recycling, which has a smaller effect on emissions. “It’s harder to get someone to ride a bike or take the bus instead of driving, compared to turning off the lights when they leave the room,” says study co-author and psychologist Matthew Goldberg, director of experimental research at the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication. “But even though it’s much harder to move, it has a really high impact.”

Bergquist and Goldberg say they would like to see more research into how various interventions compare when it comes to changing a specific behavior—for example, how social pressure compares with financial incentives in persuading people to switch to electric vehicles. Their study and future research can help policy makers decide how best to nudge people toward more climate-friendly habits. And the researchers say that different interventions can be combined to potentially move the needle even more on behavioral change, particularly because they can motivate different groups. “There’s so many routes to our goals,” Goldberg says. “And we need to take advantage of all these different routes because we reach different people.”