Bruce Willis’s family recently announced that the 67-year-old actor has been diagnosed with a progressive neurodegenerative disorder called frontotemporal dementia (FTD). The grim news helped explain the way his condition has changed since he retired a year ago because of aphasia—a disorder involving speaking and listening comprehension problems that can arise when illness or injury damages certain brain regions.

“Unfortunately, challenges with communication are just one symptom of the disease Bruce faces,” his family said in a public statement released in February. “While this is painful, it is a relief to finally have a clear diagnosis.”

Last week Willis’s wife, Emma Heming Willis, described how the family is learning to navigate dementia care. Because there is no cure for FTD, a clear diagnosis—and learning how to deal with the disorder’s inevitable progression—is basically the main lifeline that the loved ones and caregivers of people with FTD have to work with. Scientists are studying people who currently have FTD and those at risk of developing the disease to better understand what’s happening in the brain. Several drugs are currently undergoing clinical trials.

Although less prevalent overall than certain other neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s, FTD is the most common form of dementia for people under age 60. It tends to strike earlier than other dementias: Alzheimer’s usually appears in a person’s mid-60s or later, but FTD typically emerges between the ages of 40 and 60. It affects an estimated 60,000 people in the U.S. alone.

The term FTD refers to a cluster of disorders that affect the brain’s frontal and temporal lobes—regions associated with personality, behavior, language and other high-level brain functions. The disease can be devastating for people with FTD and their spouses, children or grandchildren, says Elizabeth Finger, a neurologist and professor at Western University in Ontario. One of FTD’s most insidious aspects is the way it can suddenly seem to alter someone’s personality.

“Physically they may be fine for quite a while, so it’s as though families almost have a stranger living with them,” Finger says. “Once families get the diagnosis, it helps, because often they’ve been living with that alienation for a while, and now at least they can understand this is a brain disease, and it’s out of the patient’s control.”

What Are the Symptoms of FTD?

FTD has several variants. Each is characterized by a set of symptoms linked to the location in the brain where the disease begins. The behavioral variant, which is linked to changes in the frontal and temporal lobes, is the most common. It includes symptoms such as apathy, emotional blunting, impulsivity and problems with decision-making and judgment.

Variants associated with changes in language abilities are known as primary progressive aphasia and typically involve the dominant frontal and temporal lobes (for most people, these are on the left side of the brain). These variants come in three main subtypes: semantic, nonfluent and logopenic. The semantic subtype primarily leads to a loss of word comprehension. An affected person’s vocabulary declines over time, making it increasingly difficult for them to read, write and understand conversations. People with the nonfluent subtype have trouble speaking but retain the meaning of words. In the early stages of this subtype, people may have difficulty pronouncing words and slur their speech. In advanced stages, they may stop speaking altogether. Those with the logopenic variant struggle to find the right words during conversation. As the disease progresses, these individuals may have a hard time understanding complex sentences.

Impaired movement is the most prominent symptom of the other variants. This sometimes occurs when FTD emerges alongside amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), a neurodegenerative disorder that leads to a progressive loss of neurons involved in movement.

All these variants overlap to some extent, says Yolande Pijnenburg, a neurologist and a professor at Amsterdam University Medical Centers. “The syndromes are most distinguishable when they are in their beginning states,” she says. “But when they are more advanced, they start to look more like each other.”

Pinning Down Causes

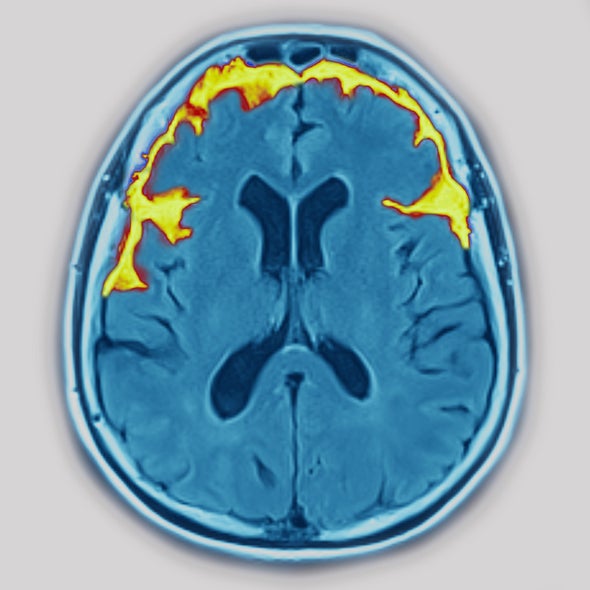

FTD is generally associated with the loss of neurons in the brain’s frontal and temporal lobes. But what causes that loss? Postmortem examinations of the brains of people with FTD have revealed that the condition is primarily linked to abnormal accumulation of two proteins: tau and TDP-43, both of which are also believed to be involved with Alzheimer’s. Scientists have found other proteins that could be responsible for FTD, but alterations in tau and TDP-43 account for more than 90 percent of cases altogether, says Chiadi Onyike, a neuropsychiatrist at Johns Hopkins University.

Studies suggest that a genetic mutation is the cause of FTD in approximately a third of affected people. More than a dozen mutations are linked to the condition, and the most common appear to be in specific genes that lead to abnormal accumulations of tau and TDP-43.

But scientists know little about what causes disease in the other two thirds of affected people without a hereditary condition, those who have so-called sporadic FTD. The only risk factor yet identified is a history of concussion or traumatic brain injury, Finger says. But that only explains a small proportion of the risk, she adds, because the majority of people with FTD have not had such brain injuries—and most people who have had them do not get FTD.

Knowing the Signs

There are several challenges in diagnosing FTD, according to Pijnenburg. It currently takes an average of 3.6 years for people to receive an accurate diagnosis of the condition. Most who have FTD, in particular the behavioral variant, do not realize that a change is taking place and rarely seek medical help on their own. Another problem is that such behavioral changes can have alternative explanations such as depression or another mental health condition. Importantly, Pijnenburg says, there’s a relative lack of public awareness about the disease.

A definitive FTD diagnosis is only possible if investigators perform a postmortem brain examination, Finger notes, or if a person carries a so-called autosomal dominant mutation, in which a single copy of a mutated gene can lead to the disease.

But there are other tools for assessing FTD, including neurological and psychiatric evaluations, neuroimaging, genetic screening and analysis of a person’s medical history. Neuroimaging techniques such as magnetic resonance imaging or positron emission tomography can reveal FTD-indicating signs of damage or functional abnormalities in the brain. Genetic screening can identify FTD-associated mutations in the subset of people with FTD who have them. According to Pijnenburg, these techniques can accurately pinpoint somewhere between 74 percent and 93 percent of FTD cases.

Researchers around the world are now studying people who carry genetic mutations linked to FTD but have no symptoms. This is an attempt to understand how the disease arises and to potentially help develop treatments, including therapies that could slow, stop or even prevent the disease.

In Canada and several European countries, a research consortium called the Genetic Frontotemporal Dementia Initiative (GENFI) has been conducting a study that follows more than 1,000 people with FTD-related genetic mutations. The group is trying to determine how early changes can be detected in asymptomatic individuals who have been deemed to be at risk, says GENFI coordinator Jonathan Rohrer, a neurologist at University College London. Now, 10 years into the study, Rohrer says behavior and brain pathology observations so far indicate that subtle changes in cognition and brain structure can occur years before the onset of symptoms.

GENFI joined forces in 2019 with researchers based in the U.S., Australia and several countries in Asia, South America and Africa to form the Frontotemporal Dementia Prevention Initiative (FPI), Rohrer says. The teams involved are pooling their data to create an international registry of FTD research participants who can be enrolled in clinical trials. Eventually the global research effort plans to prepare for clinical trials of treatments that might prevent people from ever developing FTD symptoms.

Testing new treatments

Studying people with genetic forms of FTD has already led to a variety of potential disease-modifying treatments, and some are being tested in clinical trials. These include a phase 3 trial for a treatment targeting progranulin, a multifunctional protein whose decreased levels in FTD leads to an accumulation of TDP-43. Trials are also underway for therapeutics aimed at either restoring or tamping down the activity of the known FTD-related mutated genes.

Scientists hope that if these treatments work, some may also be used to help people with sporadic FTD. “Because of the similarity in the underlying molecular pathology, there’s a growing idea in the field that therapies for genetic forms may be translatable to sporadic forms,” Finger says.

But Rohrer notes that before that happens, scientists must overcome another big obstacle to treating sporadic FTD: identifying biomarkers—such as those that can reveal tau or TDP-43 proteins in blood and spinal fluid or through imaging—in order to determine which pathological processes are at play.

For now there are ways to manage and treat specific FTD symptoms. One key facet of current care is family and caregiver education. Other approaches include psychotherapeutic and pharmaceutical interventions that target specific behavioral or cognitive symptoms and speech difficulties. Physical or occupational therapy can address language and movement problems, while changes to lifestyle or environment (such as limiting driving or credit card use, maintaining calm surroundings and providing structured routines) can help with behavioral symptoms. Onyike says researchers are also beginning to look at ways to help boost brain function—for example, by combining speech therapy with brain stimulation in people with aphasia.

Although no disease-modifying treatments are yet available, researchers find some promise in the progress of therapeutics in recent years. “We’re optimistic, and we’re making headway,” Onyike says. “Ten years ago clinical trials were about medicines to dial down symptoms or boost cognition. Today they are about stopping neurodegeneration—and doing brain rehabilitation.”