Even before the COVID pandemic, antimicrobial resistance, in which microbes no longer respond to common medications like antibiotics, was a big concern for public health organizations and health care specialists. In 2019, the latest year for which data are available, antimicrobial resistance led to 4.95 million deaths globally, making it the third leading cause of death after cardiovascular diseases and cancer.

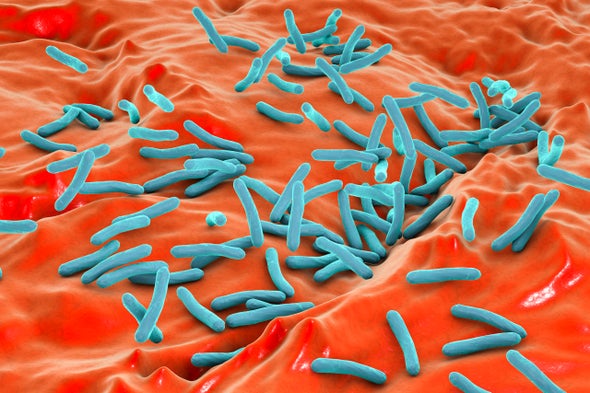

After more than two years of COVID, with rampant and inappropriate antibiotic use arising from treatment protocols, public health and health care specialists say antimicrobial resistance is getting substantially worse in many countries. This is concerning because bacteria that cause routine infections in the blood, lungs and urinary tract, not to mention well-known illnesses that still exist in lower-income nations, such as typhoid and tuberculosis, are becoming increasingly resistant to existing drugs. At the same time, the pharmaceutical industry lacks sufficient interest in developing antibiotics, as the market for them is not lucrative. We stand to lose 10 million people each year worldwide by 2050 from diseases that we could once treat. Unfortunately, 90 percent of these deaths will happen in low- and middle-income countries.

Antimicrobial resistance has been a long-standing pandemic of its own that has been overlooked. COVID has reinforced the urgency of breaking the culture of liberal antibiotic use. We must strengthen regulations around prescribing these drugs and retrain health care providers all over the world to be more stringent in their use of anitbiotics. We must improve sanitation and hygiene to prevent the spread of disease-causing bacteria. We need better diagnostics and more robust vaccine programs. We are running out of options, and the infectious bacteria that plague so many people in non-Western nations are poised to win a battle we once had in hand.

Take India, the largest consumer of antibiotics in the world, and a place where the culture of antibiotic use is deeply entrenched. Doctors prescribe an antibiotic for illnesses such as the common cold or diarrhea and even short fevers. These prescriptions are spurred by a variety of factors that include a lack of appropriate knowledge about when to use antibiotics, lack of diagnostics, inability of patients to afford diagnostics, economic incentives, patient demand and fear of clinical failure.

Pharmacists, who also serve as a first stop for health care in many parts of India, do the same since antibiotics there are commonly available without a doctor’s prescription. But these drugs often fail to work, because the majority of these sicknesses are viral not bacterial. Yet, because of these practices, the general public believes they will.

It is not surprising, then that India, given its population of more than one billion, and its easy access to antibiotics, struggles with widespread misuse of antibiotics. Further confusing the matter is the nation’s high burden of bacterial infections where antibiotics are warranted. Yet, because of widespread misuse, infectious bacteria are developing defenses against these drugs. So, while they are needed, they are losing their power.

The COVID pandemic has aggravated this practice of antibiotic misuse. Despite COVID being a viral infection with low rates of secondary bacterial infection, the pandemic likely contributed to people in India taking about 216 million excess doses of antibiotics during the first wave in 2020. This, despite World Health Organization (WHO) advice and the Indian government’s National Treatment Guidelines recommending against the use of antibiotics, especially for mild and moderate COVID cases. This practice extended to subsequent COVID surges involving the Delta and Omicron variants, and it has potentially worsened the resistance problem in the country.

India isn’t alone. Researchers have seen similar practices of antibiotic misuse in other countries that are not high-income, including Bangladesh, Pakistan, Brazil and Jordan.

We mentioned several solutions to this problem earlier, but the most important thing we can do is to change culture—the attitudes and approaches among health care providers and the general public toward antibiotics in low- and middle-income countries. For example, in these nations, acute upper respiratory tract infections that are likely viral account for the majority of unnecessary antibiotic prescriptions, yet for most health care providers, national standard treatment guidelines are not available; even when they are, these guidelines are not user-friendly and do not explain responsible antimicrobial use, making them difficult to use in a day-to-day physician’s practice.

Toward this, in 2017, the World Health Organization initiated the AWaRe (Access, Watch and Reserve) framework for antibiotics, which classifies the drugs according to the risk of resistance arising. The WHO will soon release a reference book on antibiotics with simple infographics and a mobile app, which will provide best practices in clinical assessment, diagnosis and treatment of various infections in the outpatient and hospitalized patients using what’s called a traffic-light approach. Recent evidence from China has shown that a traffic-light approach to clinical guidelines for upper respiratory tract infections reduced antibiotic prescribing from 82 percent to 40 percent in the intervention group, compared to 75 percent to 70 percent in the control group.

However, changing human behavior and overcoming decades of misaligned practice is challenging, especially among already practicing physicians, particularly practitioners who are in the informal and private health sectors. Mystery client studies, in which trained people visit facilities in the assumed role of clients and then report on their experiences, show a big know-do gap in many countries—a gap between what providers say they would do for a given patient, versus what they actually do in routine clinical practice.

Governments and health systems will need to do more to prevent over-the-counter sales of restricted drugs and direct drug sales by pharmaceutical companies to people who do not have medical training, as well as help to ban irrational fixed-dose combination drugs and work harder to prevent counterfeit medications from entering the marketplace. At the same time, they have to help introduce programs to facilitate the responsible use of antimicrobials in hospitals and in primary care settings.

India is another example of how regulations help. The country’s 2018 ban on antimicrobial fixed dose combinations in India has been successful in reducing sales of antibiotics. Similarly, banning over-the-counter sales of antibiotics led to a reduction in antibiotic sales in Brazil and Chile when properly enforced.

Besides continued efforts to improve antibiotic utilization among existing prescribers, now is the time to prepare next-generation physicians to be better antibiotic stewards. These drugs are a finite resource and affect society greatly if used inappropriately. Additionally, medical schools and training programs need to teach physicians to utilize standard treatment guidelines when prescribing antibiotics. Focusing on next-generation physicians will have a domino effect among the public, pharmacists and informal health care providers. This will safeguard us from future antimicrobial resistance pandemics while we deal with the current one.

This is an opinion and analysis article, and the views expressed by the author or authors are not necessarily those of Scientific American.