Every woman with endometriosis has an origin story, a memory of the first time she knew the pain in her pelvis could not be normal. For Emma, it goes back to the day in 10th-grade history class when she blacked out. The sensation, she says, was how a pumpkin might feel when its insides are scraped. Her gynecologist assumed she was having bad period cramps and gave her birth-control pills. They helped but not enough. “He made me feel as if I were acting a little crazy,” says Emma, now in her late 30s, who asked to go by a pseudonym. “It struck me much later that when a woman's medical problem isn’t clear-cut, she just isn’t believed.”

Not until about six years after the blackout did she find a doctor who recommended laparoscopic surgery of her abdomen to look for the cause of the pain. That is when she learned she had endometriosis, a disorder in which tissue normally found in the uterine lining, called the endometrium, escapes and takes root in other parts of the body. By then, the disease had carpeted her pelvic organs like kudzu.

In describing endometriosis, ecological comparisons seem apt. Just as the creeping kudzu vine wraps itself around trees and shrubs, smothering anything in its path, so, too, do adhesions (scar tissue) that form when wayward endometrial cells land where they are not supposed to. These adhesions can engulf or bind the bladder, the intestines, the ureter tubes leading to the kidneys and other pelvic organs. Lesions that are surgically removed often grow back: more than half of women who have them cut out return for another operation within seven years. When surgeons go in, they might see the bowels, ovaries and sciatic nerve bound in a macramé of scar tissue or a fallopian tube squeezed so tightly that an egg cannot pass through.

.png)

Despite the manifest damage it can cause, endometriosis is a mystery. Doctors know that it runs in families and is linked with several genetic variants—heritability hovers around 50 percent—but genes cannot yet explain its occurrence or predict its path. The degree of scarring and the number and location of lesions have little to do with the severity of the symptoms, which, besides pain, can include heavy bleeding, discomfort during sex and bowel movements, and often devastating infertility. Some patients find relief in surgery and drugs, whereas others, even with few lesions, try every known remedy and still live in constant pain.

For decades endometriosis has been ignored, and research into it has been underfunded. Endometrial pain and other symptoms reduce women's productivity at work by nearly 11 hours a week—27 percent of a 40-hour work week—according to results released in 2011 from the Global Study of Women's Health, which surveyed more than 1,400 women in 10 countries.

Finally, patient advocacy, social media activism and women-led movements for social change have brought attention to the problem, and the medical community has begun to reckon with its history of underestimating and undertreating women's health issues. Researchers are developing tools to study the complicated origins of endometriosis, to diagnose it and to design targeted treatments. Yet even at a time when women are raising their voices for better care, too many remain undiagnosed and in pain.

The Invasion Conundrum

“First, how does the tissue get outside the uterus?” asks Linda G. Griffith, a professor of biological and mechanical engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. As scientific director of the M.I.T. Center for Gynepathology Research and an endometriosis patient herself, she is deeply vested in the question, which has perplexed her fellow scientists for decades. No one knows for certain how or why endometrial cells show up outside the endometrium.

The prevailing theory, called retrograde menstruation, was proposed nearly a century ago. John Sampson, a gynecologist, observed that menstrual fluid containing cells from the uterus can flow backward up the fallopian tubes. Bits of that fluid, he suggested, stick to pelvic organs and the abdominal lining or float in pelvic fluid and spread to distant sites. It happens to just about every woman and is normally cleared by the immune system. But sometimes, Sampson's theory goes, the cells implant wherever they land. The misplaced tissue acts as if it is still in the uterus: it sprouts hormone receptors and responds to hormonal signals. Every month it grows as the uterine lining grows, secreting hormones, and sheds when the cycle ends. But unlike a period, the blood and tissue get trapped in the pelvis and trigger inflammation. Over time the inflammation leads to scarring and adhesions.

Ever since Sampson, researchers have been divided about the underlying cause of the disease. Is the defect in the “seed,” the rogue endometrial cells, or is it in the “soil,” the abdominal environment where those cells implant and spread? Theories on the seed side blame defective endometrial cells or stem cells. The soil side claims that endometriosis is primarily an immune dysfunction. A third theory splits the difference, saying, essentially, that the soil changes the seed. “Women with endometriosis may have had normal endometrial cells until the lesions took root and created changes in the tissue,” Griffith explains, suggesting that the immune response to the lesions is the likely driver. The resulting inflammation may alter the expression of progesterone and estrogen receptors in endometrial cells: as a result, cells pump out more estradiol, a form of estrogen that fuels growth of lesions, unchecked by progesterone. In a baboon experiment in 2006, researchers were able to induce endometriosis by injecting normal uterine lining into the pelvic cavity.

Kevin G. Osteen, a professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Vanderbilt University, has proposed that environmental toxins play a role, at least in some cases. His research focuses on one of the most toxic of environmental pollutants, the industrial by-product dioxin, and dioxinlike chemicals called polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), which are found in meat, fish, dairy products and, in varying amounts, all our bodies. Osteen's theory is that exposure to these toxins in utero disrupts the physiology of the developing endometrium. When he and his colleagues exposed human endometrial tissue to dioxin in a series of experiments, the tissue became resistant to progesterone and prone to inflammation. Without progesterone to tamp down enzymes known as matrix metalloproteinases, which regulate the monthly rebuilding of the uterine lining, endometrial tissue may become invasive, spreading beyond its normal domain in the uterus.

Griffith suspects that whatever caused her endometriosis, it happened early in life. Retrograde menstruation may apply to many cases, she says, but probably not hers. She developed harrowing symptoms from day one of her first period, long before lesions from menstruation had time to develop. Some researchers argue that patients in this category may have had a retrograde flow of endometrial cells during the normal vaginal bleeding that often occurs shortly after birth in female infants. Or when baby girls are still in the womb, endometrial-like cells or stem cells could have landed outside the uterus, sometimes as far afield as the lungs and brain (evidence of these wandering cells has been found in miscarried and aborted fetuses). “Those cells could sit there until the girl starts going through puberty,” Griffith explains—like ticking time bombs.

Similar to cancer, endometriosis has many causes and manifestations. As Griffith puts it, “It's likely not one disease but many.”

An Ecosystem of Pain

When women talk about endometriosis, they talk about pain. They talk about the sick days from school or work, lost time and opportunities, the diminishment of life's pleasures. They talk about arranging their calendar around their period or a night on morphine in the ER. One of the hardest things for them to hear is that the pain is “all in their head.”

Female suffering has a history of being downplayed by the medical establishment. In 2008 a study in the journal Academic Emergency Medicine found that women wait longer than men in emergency rooms before receiving treatment for the same abdominal pain, and they are 13 to 25 percent less likely than their male counterparts to receive opioid painkillers (after controlling for age, race, triage class and pain score). An earlier study of cardiac patients found that nurses were likelier to administer painkillers to men and to give women sedatives. And even when women do get painkillers, the medication may be less safe and effective for them because many pain studies have been conducted on men or male mice.

Even after finally getting a diagnosis, Emma lost an ovary to endometriosis when she was 26. A decade later she gave birth to a daughter and is now relatively pain-free but not without regret about the years she spent misdiagnosed and undertreated. “If I could redo my life,” she says, “I’d have pushed for answers sooner.” She did not know that endometriosis even existed when her pain first started. Nor, it seemed, did her doctors, she says.

One reason doctors and even patients minimize pain caused by endometriosis is that it flares up during menstruation when women are “supposed” to feel bad. “Pain is very subjective. Cramps are the only pain that is considered ‘normal,’ and it's hard to know when that pain is abnormal,” explains Hugh S. Taylor, chair of obstetrics, gynecology and reproductive sciences at the Yale School of Medicine. Taylor adds that social norms have prevented open conversation about menstrual pain, pain during sex or pain with bowel movements—all red flags of endometriosis. “Fortunately,” he says, “these barriers are decreasing,” and doctors, as well as patients, increasingly feel comfortable bringing these topics up and investigating their causes.

And patients can play a more active role in the fight against endometriosis. For instance, they can participate in research through the “citizen scientist” app Phendo, launched in 2016 by biomedical informatics scientists at Columbia University. Users track and identify their patterns and triggers, and the data will be used to study the disease's causes and to design treatments.

“For decades endometriosis advocates have been cultivating communities that empower, inform and educate patients,” says Casey Berna, a patient advocate and organizer. “Now there is a movement to reject historically paternalistic approaches to care and to include the patient voice, especially when managing complex diseases.”

In April 2018 Berna and her colleagues organized a protest by patients outside the Washington, D.C., headquarters of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), demanding its member doctors be better trained to diagnose endometriosis and to get patients the best and latest treatments—to stop, for instance, prescribing needless hysterectomies. “To put it plainly,” Berna says, “the current standards are responsible for decades of suffering endured by millions of patients. We’re calling on the ACOG to work with patient advocates and endometriosis experts to utilize all of their resources to address this crisis of care.”

Experts agree that too many physicians still miss the disorder. “Pediatricians and most primary care doctors are [still] not well educated about endometriosis,” Taylor says. And when endometriosis goes undiagnosed, it often worsens. “Misplaced endometrial tissue has higher than usual levels of aromatase, an enzyme that makes the lesions estrogen-dominant, which in turn drives their growth,” explains Pamela Stratton, a gynecologist and surgeon at the National Institutes of Health. The lesions also become resistant to progesterone, which would otherwise help curb endometrial growth and fight inflammation. As a result, inflammation reigns: prostaglandins (lipids that form more quickly when tissue is damaged) and pro-inflammatory proteins called cytokines act on nerve endings and ratchet up pain sensitivity. Over time adhesions form and interfere with the function of pelvic organs, causing more pain.

One of the strange features of endometriosis pain is that it bears little relation to the severity or location of the lesions. A woman with few lesions may feel as if her pelvic organs are being pulverized in a meat grinder, whereas a serious “stage IV” patient with lumps that protrude from her belly may be pain-free. Doctors may overlook adenomyosis, which occurs when endometrial tissue invades the muscle wall of the uterus; lesions here are difficult to see during surgery, but the patient is in eye-popping agony. For many women pain persists even after lesions have receded or are surgically removed.

At this point, the problem is not just in the pelvis anymore, Stratton explains; now it is a central nervous system disorder. All too often with endometriosis, the brain has been tuned in to pain for so long that it cannot turn off, even after the pain trigger is gone. In this condition, called central sensitization, neural wiring has effectively remodeled itself to be “alert to hurt.” Any minor disturbance, including ovulation, menstruation and sex, triggers and perpetuates the pain. Genetics may play a role, Stratton notes, but the details are not well understood. Women with few or tiny lesions can still suffer debilitating chronic pain, leading to central sensitization, she says. A troubling irony is that these women may be the most likely to have a doctor tell them there is nothing wrong because many gynecologists are unaware of the possibility of central sensitization. “Because they are not neuroscientists,” Stratton says, “they don’t consider what neuroscientists have learned about pain.”

Stratton, who straddles both worlds, is exploring treatments to address pain and perhaps reverse central sensitization in endometriosis patients. If a drug can relieve pain for an extended period, she posits, the central nervous system may be able to reset its pain threshold. Stratton is conducting a clinical trial of botulinum toxin, commonly known as Botox. Injected in the pelvic floor, it relaxes muscle spasms and may alter the chemicals involved in pain signaling. Although the full study will not be complete until 2020, she says, her group released a proof-of-concept study with promising results: 11 of 13 patients reported pain as mild or nonexistent within two months postinjection; for seven, relief lasted five to 11 months.

The stakes are high. Chronic pain causes sleeplessness, anxiety, depression, irritability and brain fog. Several neuroimaging studies have found alterations in the gray matter of chronic pain patients, including loss of volume in the hippocampus (which may explain memory impairment) and the prefrontal cortex (which may underlie deficits in pain regulation and cognitive function). A small study of endometriosis patients with chronic pelvic pain found shrinkage in the thalamus, insula and other regions associated with pain modulation. Tracking chronic back pain patients, Northwestern University researchers compared the loss in gray matter volume—1.3 cubic centimeters every year—with the effects of 10 to 20 years of normal aging.

A Blight on Fertility

When women with endometriosis talk about their fears, infertility ranks high. About half of women with infertility have endometriosis. In a cruel trick of nature for those who struggle to conceive, endometriosis pain is said to feel like labor pain. A blockage of the fallopian tube can avert the passage of the egg from the ovary to the uterus, and inflammation from scarring or surgery around the ovaries can compromise egg follicle quality and quantity. Pro-inflammatory cytokines and other elements in the peritoneal fluid surrounding the pelvic organs can reduce sperm motility in the fallopian tubes and damage eggs and embryos. Problems can arise in the hormones, too. Conception is a hormonal and immunological symphony; in endometriosis, the conductor has left the room. Normally after ovulation, the concentration of estrogen receptors in the uterine wall dwindles to prepare for implantation. Progesterone rises, cueing the endometrial lining to receive and nourish the fertilized egg. The hormone calms the uterus and prevents contractions. (The root of progesterone is “progestation.”) But in endometriosis, the uterine lining is resistant to progesterone, and the competing hormone estradiol remains dominant, among other factors that make the environment less receptive to a blastocyst. Even if implantation occurs, progesterone resistance may lead to a higher risk of miscarriage and premature birth.

Adding to the complexity are clues that the endometrium has a microbiome, which also becomes disordered in endometriosis. Recent studies suggest that Lactobacillus bacteria dominate the uterus in most women and have a part in implantation and support of the growing embryo. The idea remains speculative, but chronic inflammation caused by endometriosis may kill off lactobacilli, creating a microbial imbalance in the uterus that perpetuates inflammation and potential infertility. In 2016 a preliminary investigation published in the American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology found that when non-Lactobacillus microbes dominate, as they do in endometriosis, implantation occurred at only one third the normal rate, and the number of miscarriages shot up. Although the cause of the connection is not clear, studies such as this one have inspired research into the role of the endometrial microbiome in endometriosis, and some doctors may consider testing endometrial cultures before fertility treatment.

There are success stories, too. Approximately 43 to 55 percent of endometriosis patients are able to conceive through one cycle of in vitro fertilization (IVF), depending on the stage of their disease, and women with endometriosis who do become pregnant through IVF have similar live birth rates to those without the disease. In the hormonal milieu of pregnancy, symptoms usually subside. Breastfeeding, too, is linked with a lower risk of endometriosis. This 2017 finding, derived from a data set of more than 70,000 women, showed that for every three months of exclusive breastfeeding, the risk of a woman developing endometriosis drops by 14 percent, compared with breastfeeding for less than a month. It remains an open question whether lactation-related hormones and immunological factors can relieve the symptoms of women who already have endometriosis.

Better Tools and Treatments

When scientists talk about endometriosis, they always bring up the seven-year hitch: the average lapse between the onset of pain and a diagnosis, by which time a lot of damage may be done. A diagnosis currently requires a surgical procedure (laparoscopy), but the disease could be caught much earlier if it could be identified with a simple blood, saliva or urine test. The challenge is to find the right signal to look for.

In recent years several laboratories have homed in on microRNAs (miRNAs): short, noncoding sequences of RNA that regulate gene expression and are shed by tissues. In 2016 Taylor's group identified three miRNAs that are more prevalent in endometriosis patients, compared with control subjects. Taylor's company, DotLab, will use these miRNAs as a basis for the first diagnostic saliva test for endometriosis, which Taylor says has an accuracy of well over 90 percent. The lab recently got a new round of funding, and the test, administered by prescription, is poised to launch in the near future. If it succeeds, women may receive treatment earlier, Taylor says, and doctors may also use it to discern whether a drug they prescribe is effective. After all, a diagnosis, early or not, does not ensure relief. Some drugs work at first, then lose effectiveness. Others trigger menopauselike symptoms.

In the future, a newly diagnosed patient might start her treatment with a skin biopsy, envisions Julie Kim, a professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Northwestern University. Cells gathered from a tiny skin punch in a woman's thigh or lower hip would be engineered to travel backward in developmental time to become induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells, which can grow into any cell in the body: endometrial cells, liver cells, kidney cells, and so on. Each cell type would be used to seed a “micro organ” on a tablet-sized electric circuit that represents her body—in other words, her medical avatar.

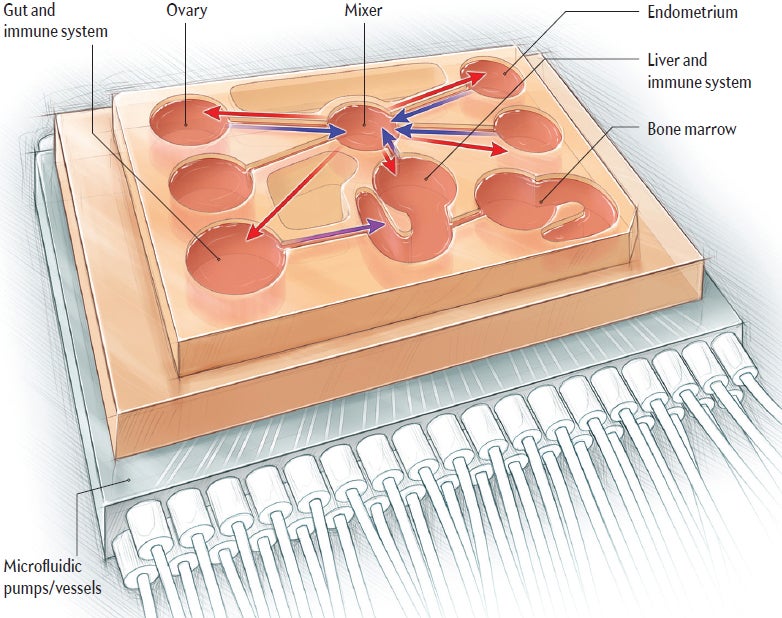

Several organ-on-a-chip avatars are already here. The one Kim built as co-investigator resides at the Woodruff Lab at Northwestern: the EVATAR (a mash-up of “Eve” and “avatar”). It is a miniature female reproductive system, complete with micro ovaries, fallopian tube, uterus, cervix and liver. Like other patient avatar platforms, the EVATAR's “organs” are harbored in dime-sized vessels that sit on a plate connected to a computer. Artificial blood flows through minuscule channels connecting the organs, carrying hormones, nutrients, and growth and immune factors. The EVATAR has a monthly cycle but does not bleed.

A patient with an EVATAR would know which drugs are likeliest to help her; after all, every micro organ on the platform holds her specific genetic blueprint. “Say we’re testing a drug designed to reduce endometrial lesions,” proposes Kim, describing the kind of study she anticipates doing with the EVATAR. Her lab would expose the system to the experimental treatment. During the menstrual cycle, the scientists would collect and analyze data from each organ to see, at the cellular level, if the drug is safe and effective against that patient's lesions. This kind of experiment also avoids the problem of many drugs and treatments being tested on men and animals and then not translating to women and opens the door to custom medicine.

Kim's lab has shown a proof of concept with the EVATAR, but developing an endometriosis platform and testing drugs could take up to five years, Kim says. It may be longer before the platform can test individual patients; the time line depends on many factors involved in taking a research tool to the clinic. The project can only work, she says, “if the resources are available and there is a priority given to endometriosis research.”

In Griffith's view, custom drug testing on individual patient avatars is prohibitively expensive, but organs on a chip still have a role to play in figuring endometriosis out. Instead of using an organ-on-a-chip platform for each patient, Griffith hopes to classify women with endometriosis by several molecular markers, similar to what is done for breast cancer, then develop drugs that target each type. “All patients are different,” she says, “but we believe there may be groups of patients with common features.”

The first step toward finding those groups, Griffith explains, is to build computer disease models and a few hypothetical classification schemes. Next, she would recruit hundreds of patients from multiple clinics and test those models on them. Griffith predicts that three to five groups will emerge that have different types of dysfunction, each with characteristic molecular signatures.

Griffith's organ-on-a-chip platform—called PhysioMimetics—can connect up to 10 mini-organ systems on an integrated circuit, including a tiny endometrium designed by Christi Cook, a former Ph.D. student in Griffith's lab. The chip endometrium consists of a polymer “hydrogel” scaffolding that supports several layers of endometrial tissue cell types. Researchers can apply various hormones and inflammatory cues to the tissues to see what happens.

Once Griffith has identified her disease-type groups—each with its own unique molecular markers—she plans to use the organ-on-a-chip platform and partner with pharmaceutical makers to test drugs that target the specific disease pathways in each group. If the drug appears to be safe and effective on the avatars, she will try it on flesh-and-blood patients.

Despite the promise of organs on a chip and other tools, however, the medical community has a long way to go to fight endometriosis effectively. Funding for research on the disorder is still incommensurate with the disease's societal costs: $62 billion annually in the U.S., including lost work productivity and direct health care costs, according to a 2012 study by the World Endometriosis Research Foundation. An NIH report shows that in the U.S., nearly $1 billion will be spent on diabetes research in 2018, compared with $7 million on endometriosis, which afflicts about the same percentage of women. “If you look in PubMed,” the online archive for biomedical studies, Griffith says, “you will find more than 20,000 papers for erectile dysfunction but only about 2,000 papers on adenomyosis, which is estimated to be as common as endometriosis. Who misses work for the first one?”

Fortunately, Griffith says, talent is attracted to the field because the research is “fascinating scientifically”—and also happens to be crucial to society. After all, there is no cure yet: the closest thing is a surgical absence of disease, to which Emma would add, “And a subjective absence of pain.” When chronic pain goes away, the mind heals. Gray matter can and does regrow. But like kudzu, endometriosis is tough to subdue—beating it back will take a concerted effort by researchers and doctors, as well as a real financial commitment from a society finally ready to take this disorder seriously.

*Editor's Note (6/26/18): This sentence from the print edition was edited after posting online to correct an error in the reported percentage of a 40-hour work week.