When Ella time traveled in my office for the first time, I did not realize what was happening right away. She was sitting comfortably in a chair, her hands folded, her back straight and her feet flat on the floor. There was no dramatic change, no shuddering or twitching. But then I saw it: a slight shift in how she held her body. Her face softened almost imperceptibly. I heard it, too: her voice sounded different, pitched just a teeny bit higher than usual, with a new singsong quality. At first I found it curious. As it continued, I felt a growing sense of unease. Acting on a hunch, I asked her how old she was. “I'm seven,” she said. Ella was 19.

I'm a licensed clinical social worker specializing in trauma, eating disorders, self-harm, personality disorders, and gender and sexuality issues. I am also a cultural anthropologist with expertise in the intersections of culture and mental health. Ella (I have changed her name here to protect her privacy) was referred to me by a concerned university colleague who taught her in one of her classes. Ella and I began meeting for twice-weekly therapy sessions, which eventually increased to three times a week. We worked together for four and a half years.

Ella came for help with complex post-traumatic stress disorder. She was a survivor of long-term, severe childhood sexual abuse by a trusted religious leader. She had nightmares, flashbacks and anxiety, and she engaged in various forms of self-harm, among other symptoms. But there were other things going on. Ella regularly missed pockets of time. She “spaced out” unexpectedly, “waking up” wearing different clothes. She experienced intense thoughts, emotions and urges that felt like they were coming from someone other than herself.

In a way, they were. Ella, it eventually became clear, had dissociative identity disorder (DID), a clinical condition in which a person has two or more distinct personalities that regularly take control of the person's behavior, as well as recurring periods of amnesia. Popularly known as “split” or multiple personalities, DID and its criteria are listed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), the authoritative psychiatric compendium published by the American Psychiatric Association. Over time Ella manifested 12 different personalities (or “parts” as she called them) ranging in age from two to 16. Each part had a different name; her own memories and experiences; and distinctive speech patterns, mannerisms and handwriting. Some communicated in words, and others were silent, conveying things through drawings or using stuffed animals to enact scenes. Most of the time the different parts were not aware of what was happening when another part was “out,” making for a fragmented and confusing existence.

DID is a highly controversial diagnosis. Patients with DID symptoms are frequently dismissed by clinicians and laypeople alike as faking or neurotic, or both. This kind of skepticism has been fueled by the case of “Sybil,” who became the subject of a 1973 best-selling book; later evidence indicated she was faking her condition. My diagnosis of Ella was based on the DSM-5 criteria, her score on various psychological tests of dissociation, and our years of working together. Notably, fakes have something to gain by faking. Ella had nothing but losses. Her personalities would sabotage one another, ruining relationships and threatening her school performance.

So how to help her? Therapists have traditionally treated people with DID with the goal of “integrating” them: bringing the fragmented parts back together into one core self. This is still the most common approach, and it reflects a Western view of the world in which one body can have only one identity.

This is not a universal human belief, however. People in many other cultures see the body as host to several identities. Given my anthropological training, I approached Ella's DID symptoms differently than many clinicians might. Ella looked to me like a community—a dysfunctional one at that moment but a community, nonetheless. My concern was less with the number of selves she had than with how those selves worked together—or not—in her daily life. Was it possible to bring those selves into a harmonious coexistence? Ella thought it was, and so did I, so that was the mission we embarked on in therapy.

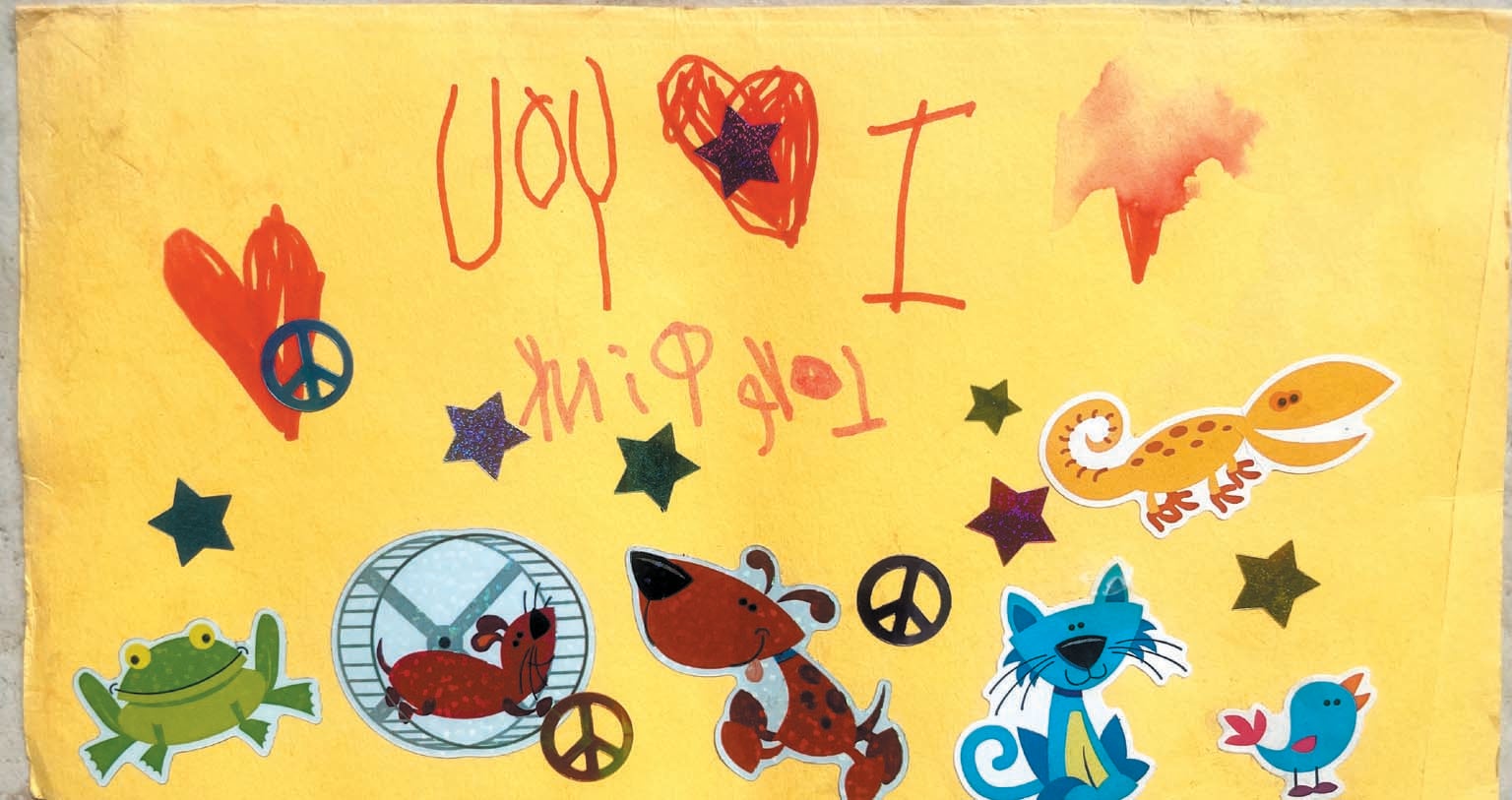

Ella didn't show up talking about “parts.” We started our therapy focused on helping her manage the everyday consequences of the abuse she had endured. Then, about a year after we began, things took an unexpected turn. Ella came into her session one day clutching several scraps of paper covered in childlike writing: shaky words with misshapen letters and misspellings. Some of the notes were written backward. “I keep finding these scattered around my room,” she told me, alarmed. “I've also found these,” she said, pulling drawings of stick figures, animals and rainbows out of her backpack, some with smiley-face stickers on them. Despite the overtly innocent tone of these materials, Ella found them frightening. She had no idea where they had come from. “I don't understand what's happening,” she told me. “I must be making them, right? But I don't remember doing it.”

As our sessions continued, Ella recounted more strange incidents. She would sometimes “wake up” in the middle of a conversation with someone and realize she was somewhere other than the place in which she last remembered being. Occasionally she would find things moved around in her room she didn't remember moving. I began receiving e-mails sent from her address consisting of strings of consonants with no vowels at all, like this:

Htsmmscrdrtnwwshwrhrblktshrndmksmflsf

These were decipherable with some effort (this one says, “Hi, it's me. I'm scared right now. Wish [you?] were here. Blanket is here and makes me feel safe”), but Ella had no memory of sending them.

That unnerving first time the seven-year-old appeared in front of me happened when Ella and I had been working together for about 13 months. After that, Ella began to dissociate into younger parts more often during therapy. Some of her parts came out in full flashback mode, feeling absolutely terrified, and had to be talked down. Other parts were silent or angry. The seven-year-old and I would sit on the floor and color or make art while we talked, sometimes about what was happening in Ella's current life, sometimes about things that had happened in the past. To distinguish among her identities, Ella asked them to use different-colored markers when they wrote or drew. The seven-year-old part chose purple as her color and as her name: Violet.

As far as Ella could discern, all these parts were versions of her at different ages. Some parts were better at dealing with certain situations and feelings than others were, and they would “come out” when those feelings were especially strong or when a situation required that part to appear and act.

Sometimes, however, the parts were in conflict. For example, a part named Ada—age 16—first appeared in the wake of a catastrophic rejection by a high school guidance counselor after Ella shared her abuse history. As a result, Ada was mistrusting and suspicious. She was also extremely rigid, moralistic and self-punishing and was quick to lash out with an acerbic tongue, including at me. She viewed herself as a protector. Violet was very different. Violet trusted easily and loved generously. She really wanted to connect with other people. These traits often put Violet and Ada at odds and sometimes led to all-out internal warfare, with Ada, the older and stronger, usually prevailing. To punish Violet, Ada would sometimes hurt “the body” by hitting and biting her arms and legs and holding a pillow over her face until she passed out, behaviors Violet experienced as a reenactment of the abuse that created her.

Psychiatrists believe that developing multiple identities protects a child—the disorder usually has roots in childhood—by keeping traumatic memories and emotions contained within specific identities rather than letting them overwhelm the child completely.

This is a contemporary understanding of DID, but people have speculated for centuries about what might cause someone to exhibit what appear to be multiple personalities (the first reliable recorded case of what we now call DID was noted in a young nun named Jeanne Fery in 1584 in Mons, France, and was regarded as a spiritual affliction). Today DID is one of several dissociative disorders outlined in the DSM-5. It is well documented and is not as rare as many people think: community-based studies from around the globe consistently find DID present in about 1 to 1.5 percent of the population.

Despite these findings, many Western clinicians do not believe that DID exists, attributing it instead to misdiagnosis or fabrication and pointing to the lack of definitive biomedical evidence for the condition. No blood test or x-ray can help us identify it, for example, and none of the standard biomedical mechanisms of evidence apply. (It is interesting that there is no biological test for schizophrenia, either, yet few people doubt that the disease exists or that people's hallucinations are genuine. The assumption of “one self in one body” isn't challenged by schizophrenia, but it is by DID.) Although brain scans show different brain structures and functions in people with DID, it is not clear whether these differences are the cause or the result of dissociation.

Another confounding possibility is diagnostic overreach and unconscious bias on the part of therapists. Despite the ambiguity of DID's presentation, striking similarities among patients who receive the diagnosis are notable. Like other dissociative disorders, DID is diagnosed primarily in young adult women, many with a reported history of severe child abuse, especially sexual abuse. This profile may indicate something about the origins of DID, but it also might reflect the way clinicians tend to label certain types of psychiatric distress in younger women. Studies have shown stark gender and race differences in diagnoses of psychiatric conditions, even among patients with the same reported symptoms. It's therefore possible that a clinician might see and diagnose DID because the client fits an expected profile.

Correctly diagnosing DID is tricky. To make an accurate diagnosis, a clinician must carefully assess the totality of a person's symptoms and rule out other possible causes for the appearance of multiple personalities, as well as the chance of a fake. This evaluation requires time and expertise. In addition to assessing whether a client meets the official diagnostic criteria, a therapist must also consider whether the specifics of the different personalities hold up across sessions over time, whether any inconsistencies suggest the presentation might be fabricated, what kind of affect is associated with or evoked by the appearance of different personalities, whether the client seems to get some secondary benefit from displaying DID symptoms—Sybil's doctor paid her apartment rent, for instance—and what role the diagnosis plays in their everyday life and their understanding of themselves.

Before working with Ella, I was agnostic about DID. I knew about the history of the diagnosis and the criticism lodged against it. I knew about factitious disorder (in which a patient makes up or deliberately induces symptoms) and malingering; about trauma, self-harm, disordered eating and dissociation; and about the careful work needed to accurately assess and diagnose any client, especially one who presents with symptoms that are complex or ambiguous. For these reasons, I did not jump to conclusions about Ella's condition. I took time—many months—to carefully assess what I was hearing in sessions and perceiving through metacommunicative cues such as body language, eye contact, posture, vocal quality and communication style. In addition to our 50-minute, three-times-a-week sessions, Ella also corresponded with me regularly by e-mail, with different parts e-mailing me (and sometimes one another) almost daily. I had no shortage of data to work with, then, in assessing Ella's condition. I kept detailed notes on our sessions and remained especially vigilant for any inconsistencies or other indications that Ella's parts were fabricated.

Over time I became persuaded that Ella's parts were indeed “real” in the sense that her discontinuities in consciousness and awareness led her to experience aspects of herself as separate personalities. I don't think she was faking her symptoms or performing what she thought I wanted or expected to see. It's possible that she was, but throughout our years of working together, I saw absolutely no indicators of it. Nor did Ella seem to take any pleasure in having parts; on the contrary, it made her life exceedingly difficult, especially in the beginning, and she often expressed significant frustration at her situation.

The next step was figuring out how to help this extremely distressed and traumatized woman. Here my anthropological training came in alongside my work as a therapist. What, I wondered, might happen if we took the “is she or isn't she?” question off the table and instead questioned our own assumptions about what makes a healthy self?

In the contemporary West, we generally think of the self as a bounded, unique, more or less integrated center of emotional awareness, judgment and action that is distinct from other selves and from the world around us. This self is singular, personal, intimate and private: it is not directly accessible to anyone but us. The self is the core of a person, the center of experience, the fundamental aspect of us that makes us who we are.

So foundational is this concept of the self to Western culture that it operates like a natural fact. It seems so self-evident that it serves as the basis of our understanding of mental health and illness. Almost every disorder outlined in the DSM-5 describes a deviation from the idealized notion of what a self is and does. “Self-disturbances” characterize conditions such as psychosis, depersonalization, borderline personality disorder, codependency, eating disorders and dissociation, among many others. Our cultural understanding of “self,” then, largely determines how we define mental illness and health.

But this understanding of the self is far from universal. Anthropologists have long documented very different ideas about the self in cultures around the world; indeed, the possibility of more than one entity residing in a body at a time is a widespread human belief. In parts of central Africa, for example, people assert that a child receives a number of different souls at birth: one from the mother's clan, one from the father's clan, and others from elsewhere. The Jívaro people of Ecuador posit the existence of three souls, each imbued with unique potential. The Dahomey, also called the Fon, in West Africa traditionally believed that women had three souls and men had four. The Fang, who live in Cameroon, Equatorial Guinea and Gabon, believe in seven souls, each governing different aspects of the person. A number of North American Indigenous communities believe some individuals are “two-spirited,” having one spirit that is female and one that is male. Some interpretations of Jewish religious texts contend that up to four souls can be reincarnated in one body. Cultures all over the world also recognize spirit possession, in which an individual serves as host to a supernatural entity.

Such views are not confined to distant lands, either. Anthropologist Thomas J. Csordas has described how some American evangelical Christians understand the presence and active participation of multiple demons and spirits within their bodies.

Dramatic accounts aside, having multiple parts, whatever we call them—entities, selves, souls—is a more mundane state than most people might think. Neuroscientist David Eagleman has described how the brain's complex system operates as a collection of individual “minds” that together produce the illusion of unified consciousness. Internal Family Systems therapy, a burgeoning evidence-based approach, posits that the mind is inherently multiple—that what we experience as “self” is really an internal system of subjectivities that shift in response to inner and outer cues and that can be engaged and transformed through therapy.

In other words, we all have parts. We even regularly talk about them without marking it as odd. As I'm writing this article, part of me is excited to share what I've learned. Another part of me is overwhelmed by other work and is mindful of all the things not getting done while I write. Another part is nervous about how my ideas—and Ella—will be received. Yet another part is eager for the engagement. That I have all these different parts of me operating at once probably doesn't raise any alarms: we are all familiar with these kinds of complexities. In this sense, I don't think Ella is that different from the rest of us, except that she has barriers between her parts that disrupt the sense of continuous consciousness most of us take for granted.

Ella was a young woman in trouble, certainly, but from my anthropological perspective, she also began to look like a community of selves within one individual. Anthropologists have ample tools for engaging with and understanding communities: we go to them, we listen to people living in them, we watch how they live and interact, and we learn.

But Ella's internal world was unlike any other community I had encountered. Most communities are composed of multiple bodies sharing the same temporal location. In Ella's case, the community consisted of one body and multiple temporal locations. Some parts existed only in the past, continually living and reliving their original traumas. Others lived almost entirely in the present, aware of when they were “made” but then going offline until they came out again years later, with few memories of what had happened while they were not in the foreground. Violet was special. She was created when the body was seven, and she had memories of the original abuse, but unlike other parts, she had remained largely present in the background of Ella's life between then and now and knew what had happened during the intervening years. With her unique perspective on Ella's internal world across time, Violet became my “key informant” in an anthropological sense as I explored Ella's community of parts.

Psychiatrist Irvin D. Yalom has said that one must create a new therapy for each client because each person's internal meaning system is different, and so each will have distinct ways of experiencing basic existential concerns. Building on Yalom's concept, we might say that each person's inner world is a unique culture with its own history, language, values, practices and symbolic systems. Approaching therapy in this way requires an anthropologically informed exploration of the client's inner world. Such work takes time and patience and is built on a foundation of trust. Like an anthropologist, a therapist must learn to speak the local language of the client's inner culture and understand the symbolic systems, ritual practices and dominant themes that reverberate in different ways in different domains. Most of all, therapists must remember that we are guests and that however much training and knowledge we may have, we can never truly know what it is like to live with that particular inner reality. The client is the true expert on her own experience. I took this approach to my work with Ella.

As I proceeded in my “fieldwork” with Ella's internal community, my earlier anthropological research in a very different context became relevant. In a book I wrote about young women entering a Roman Catholic convent in Mexico, I argued that new initiates (called postulants) came to understand their religious vocations by developing a new experience of time: they learned to read the self simultaneously across different temporal scales, one based on the everyday world and one based on the eternal time of God and creation.

The postulants are guided in reconceptualizing their entire lives as a series of events indicating a divinely directed transformation, a progressive unfolding of self that operates in both temporal registers. For example, during their first week in the convent, the postulants learned that the homesickness they were feeling was a replay of the feelings the Virgin Mary had when she left home to travel to Jerusalem. In a retreat focused on the Virgin Mary held one month before the group was to enter the novitiate, the Mistress of Postulants told them that the 10 months of the postulancy are like the months of pregnancy—that the postulants were, in a very real spiritual sense, gestating Jesus in their wombs. They became, in other words, simultaneously the daughters, brides and mothers of Christ, orienting toward a spiritual rather than a physical model of female reproduction. Learning to construct a meaningful narrative of self that embraced—rather than denied—such temporal paradoxes sat at the heart of the transformation the postulants underwent in their first year.

I saw something similar in Ella in that different parts existed at different times yet also in the present. This trait formed what Ella and I came to call a telescoping process, with parts stretching back across time, marking the discontinuity between past and present, and then collapsing it. Although some parts remained the age the body was when they were made, parts of any age could be created at any time. Once, for example, a new part showed up who was about two years old and communicated only by crying and demanding ice cream at the grocery store. In addition to telescoping time, then, identities could actively use temporal displacement in their communication. If I had not done the work at the convent or known about the anthropological research on varieties of temporal reckoning, I am not sure I would have realized what role telescoping time played in Ella's ongoing process of healing.

Ella and her parts were adamant that they did not want integration, and I did not push for it. The problem for Ella was that, at the beginning, the barriers of awareness between her parts made it difficult for her to function, and crises could occur when these different parts had different beliefs, motivations and goals. For example, one of the younger parts insisted on taking a stuffed cow to class in Ella's backpack, and Ada and Violet had to struggle during lectures to keep her from pulling it out and playing with it. Another time Ella had been working hard on a final paper for a class, and then Ada came out and deleted it because she objected to the fact that it had to do with evolution. Ella, exasperated, had to start all over. My goal with Ella's parts, then, was not integration into one self but community building.

We started with strategies to increase communication among Ella's parts, such as keeping a notebook where each part could jot down things they did while they were out so others would know what to expect when they were in charge. As time went on, parts sometimes wrote e-mails to one another (and copied me). Ella and her parts eventually were able to have “team meetings” where they came together in a meeting space she created in her mind—a living room with colorful couches and pillows and toys for the younger parts.

Even so, not everything was shared among parts: strong boundaries between the thoughts, feelings and memories of different parts remained, and things did not always go smoothly. But Ella's parts gradually learned to work as a team of specialists. One was good at taking tests, one felt at ease when talking to authority figures, one was comfortable with emotional attachment, and one felt ongoing hurt but eventually began to cry softly in the background instead of taking over and making it impossible for Ella to function. Even Violet and Ada began to team up and make lasting present-day attachments.

As Ella's college graduation approached and we came to the end of our therapy, Ella still wasn't “cured” according to the standard treatment guidelines. She was functioning well in the everyday world, although some parts (Violet, Ada, and a few others) remained present and showed no signs of going anywhere. Ella and her parts continued to insist that integration or fusion was not an option. How, then, to make sense of our work together? Was it a success or a failure?

The answer to this question is not black-and-white. On the one hand, as Ella's parts increased their collaboration, the trajectory of her life gradually began to arc forward instead of back. She graduated from college with honors, earning a degree from one of the country's top universities. She then went on to graduate school, where she specialized in working with children with a range of special needs. She excelled in this field and told me that having her younger parts still present in the background was an enormous benefit in helping her empathize with children others found frustrating or implacable. A few years later Ella met and fell in love with a wonderful partner, with whom she shared her entire history. They eventually got married and welcomed their first child.

But life is not perfect, Ella told me recently, and she still struggles with a variety of aftereffects of the trauma she endured. She is still plagued by nightmares, though not every night. The memories of the abuse remain vivid. She still feels the presence of Violet, Ada, and a few of the others, although they rarely come out anymore. She continues to take things one step at a time as her healing journey continues.

I would like to think, then, that the therapy was a success even if Ella remains, at least partially, “symptomatic.” But I emphasize that my approach with Ella might not work for everyone. Different clients can have very different needs. In Ella's case, anthropological insights helped me understand and work in collaboration with—rather than in opposition to—her inner world and envision the possibility of a healthy self that doesn't map onto the standard models.

Ella is one of those clients whose presence remains even long after the therapy has ended, and I continue to reflect on what I have learned. Ella encouraged me to share her story in the hopes that it might help others understand the realities of DID and the possibilities for finding ways forward even when the path is not well trodden. Whatever one believes about DID, Ella's story has much to teach us all about what it means to suffer unthinkable harm; to find, against all odds, a way to move on; and to be deeply, almost unbearably, human.”

An early description of Ella's case appeared in “Inner Worlds as Social Systems: How Insights from Anthropology Can Inform Clinical Practice,” by Rebecca J. Lester, in SSM—Mental Health, Vol. 2; December 2022.