Karen Oberhauser was scrambling up a mountain about 100 kilometers northwest of Mexico City when she began to fear for the future of the monarch butterfly. It was the winter of 1996–1997, and Oberhauser, an ecologist then working at the University of Minnesota and more accustomed to the flat, low-lying U.S. Midwest, huffed and puffed during the steep, high-altitude hike. Her head ached in the thin air. But when she stopped to look around, she saw millions of monarchs draped like living jewels on fir trees that hugged the slopes.

Nearly the entire monarch population was crammed into this spot and a few forests close by—just about 18 precious hectares in total. Scientists who study the butterfly knew about the location, but this was the first time Oberhauser had been to it. One freak storm or an illegal logging operation, she thought, could wipe the place out. “It made me realize how incredibly vulnerable they are,” she recalls.

That forest is the start of a remarkable annual migration that sends monarchs as far north as Canada during the summer and brings them back to Mexico every winter. Along the way they breed and feed in Midwestern farm fields near Oberhauser’s home. And during the years after her forest visit, Oberhauser began to suspect that her region had become another monarch vulnerability. Farmers were dousing corn and soybean fields there with the weed killer Roundup to wipe out many nuisance plants. But the chemical also kills a plant precious to the monarchs: milkweed, on which adult butterflies lay their eggs and the only plant that monarch caterpillars eat. Oberhauser and her colleagues began counting plants and eggs. They concluded that fewer milkweed plants in farm fields meant fewer eggs, which meant fewer adults returning to Mexico. In 2012 she co-authored a paper announcing this “milkweed limitation hypothesis” and its alarming implication: Roundup was imperiling the great monarch butterfly migration.

The public and many monarch scientists were galvanized by the idea. It made sense—a major food source was vanishing just as Mexico’s butterfly population was crashing. In the winter of Oberhauser’s visit, there had been about 300 million butterflies, but just over a decade later there were fewer than 100 million. The remedy, Oberhauser and others said, was to plant milkweed in large amounts to make up for the losses. Thousands of citizen conservationists answered the call. Michelle Obama planted milkweed in a White House garden. Environmental groups petitioned the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to list the monarch butterfly, Danaus plexippus plexippus, as a threatened species to give it more habitat protection.

But since then, some scientific cracks have emerged in the milkweed case. Monarch censuses taken in the U.S. both during and after the summer breeding season showed no steady decline, even as Mexican numbers plummeted. And many Mexican butterflies came from U.S. areas without many Roundup-soaked crop fields, other data suggested. Skeptical scientists asserted that the insects were breeding fine in northern climes but that something was taking them out on their way to Mexico. “The migration is akin to a marathon,” says Andrew Davis, an ecologist at the University of Georgia. “If the number of people who start the marathon has not really changed in 20 years but the number of people who reach the finish line has been going down, you wouldn’t conclude that the number of people is declining. You would conclude that something’s happening during the race.”

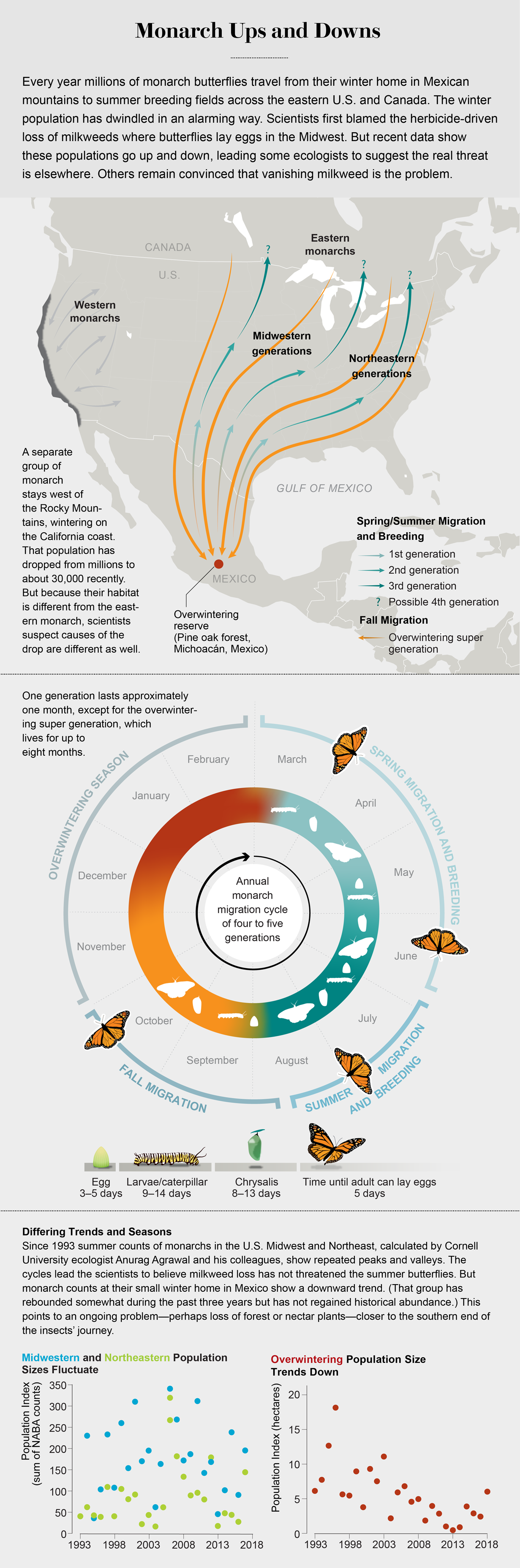

The identity of that something, however, remains an elusive and troubling mystery. Some data have suggested that landscapes have lost nectar-giving plants that adult monarchs feed on during their southward journey and that the all-important forests at the end of the migratory route have been degraded. Scientists have also speculated that a parasite infection might be cutting down the migrants. (A smaller monarch population that winters on the California coast has also crashed recently. Entomologists are concerned about this group, but its habitat does not overlap with that of the eastern population, so scientists think the causes of this crash are probably different.)

Virtually everyone agrees that overall, despite spikes and dips from one year to the next, the winter population in Mexico has been heading down for most of the past three decades. That is not good news for the monarchs. What to do about it, though, depends on the cause. Oberhauser and her allies still contend that milkweed loss is enemy number one. But the other evidence adds confusing and complex twists to what once seemed like a straightforward story with a ready-made villain. That means helping the insects has become more complicated, too.

North by South

The first definitive report of monarchs moving en masse comes from 1857, when a naturalist described butterflies appearing in the Mississippi Valley in “such vast numbers as to darken the air by the clouds of them.”

Over time biologists learned that when spring comes to the valley, as well as to other parts of North America, female monarchs alight on more than 70 species of milkweed plants (genus Asclepias) to feed and to lay eggs. One adult female can lay up to 500 eggs. When that job is done, she dies. From her eggs hatch caterpillars that turn into butterflies; the cycle repeats four to five times during a year.

Monarchs that overwinter in Mexico fly north and lay eggs near the Texas border in the spring. Their offspring live two to six weeks and spawn generations that move to the Midwest and South and ultimately all the way into the Great Lakes states, New England and Canada. As the days shorten in the fall, the last butterfly generation, dubbed the “super generation,” appears. These insects can live as long as eight months because their metabolism slows down and they do not spend precious energy on reproduction. Instead they travel south—all the way from higher latitudes to Mexico, covering up to 160 kilometers in a day. By December the insects that have survived the trip are huddled on Mexican firs. They live there until early spring, when they begin their own journey north, and their children continue the odyssey.

In the late 1970s, after a long search, biologists discovered the tiny mountainside forests where monarchs were overwintering in Mexico. The late Lincoln Brower, who worked as a biologist at Amherst College and then at the University of Florida, helped to persuade Mexican officials to place the forests under protection, launching the monarch conservation movement.

In the early 2000s Oberhauser and John Pleasants, an ecologist at Iowa State University, discovered another key monarch habitat: the farm fields of Iowa and other Midwestern states, where common milkweed plants growing between crop rows were dotted with monarch eggs. Apparently the crop fields were a massive hatchery. “That was an eye-opener,” Oberhauser says. It revealed “how important agriculture really can be, even though we think about it as a biodiversity wasteland.”

Subsequent field visits by the two researchers revealed that milkweed plants in these farm fields held up to four times more eggs than did milkweed in natural prairies and in farmland set aside for conservation. “They seemed to be monarch magnets,” Pleasants says.

American farm fields were, however, about to undergo an unprecedented ecological cleanse. Agricultural chemical company Monsanto had engineered corn and soy plants with a gene that allowed them to survive exposure to the herbicide glyphosate, better known by its trade name, Roundup. That meant Roundup could be sprayed liberally, leaving money-making crops unharmed while killing nearly everything else in a field. For farmers, “Roundup Ready” corn and soy were boons. For other plants that took up space among harvest rows, they were a death sentence. By 2007 nearly all the farmed soy and more than half of the corn in the U.S. were Roundup Ready.

Based on their Iowa data, Pleasants and Oberhauser estimated that between 1999 and 2010 the overall number of Midwestern milkweed plants had declined by 58 percent. Brower and his colleagues had reported that within that time span, overwintering monarch populations had fallen steeply. In fact, during the winter of 2009-2010 the occupied area of Mexican forest decreased to less than half of what it had been the previous year and dipped below two hectares for the first time since record keeping began in the early 1990s. The link between the two trends seemed inescapable, and it pushed Pleasants and Oberhauser to publish their landmark 2012 paper arguing that Midwestern milkweed loss was killing the monarch. Oberhauser called it a “smoking gun.”

If the paper had been about any other insect, only a handful of specialist scientists might have taken note. But the monarch butterfly has a special place in the hearts of people in three North American nations. The insect’s bright-orange color and large size, the gentle loops of its flight and, most of all, its spectacular migration have made the monarch a much loved celebrity.

And the story had a bad guy that the public was already primed to hate. Roundup’s manufacturer, Monsanto (now part of the conglomerate Bayer), embodied many people’s fears about genetic engineering and corporate control of agriculture. So the idea that Monsanto’s flagship product was killing America’s flagship insect made big news. Oberhauser and Pleasants’s hypothesis was widely covered by U.S. media outlets, including this one.

An army of conservationists mobilized to save the day. By 2014 more than 10,000 “monarch way stations” had sprouted around the country, thanks to a milkweed-planting program led by University of Kansas insect ecologist Orley “Chip” Taylor. In subsequent years President Barack Obama and his Mexican and Canadian counterparts all promised to protect the butterfly, and a few months later cameras clicked as the First Lady joined children as they planted milkweed in a special pollinator garden.

Counts that Didn’t ADD Up

But even as the milkweed limitation hypothesis gained public support, some scientists suspected it was being built on a flimsy foundation. One of the first to voice doubts was Davis, the Georgia ecologist. He had been analyzing counts of monarchs whose late-summer journeys toward Mexico took them through a handful of “funnel points”: Peninsula Point, sticking into the northern edge of Lake Michigan, and Cape May in New Jersey, a small strip of land bounded by the Atlantic Ocean and Delaware Bay. At each of these places, for several decades, volunteers have tallied south-going insects and birds at the end of summer. For monarchs, Davis noted, the numbers did not show a steady decline but bounced up and down year to year, as is typical of insect populations.

Davis’s paper got scant attention when he published it in 2012, and Oberhauser and Pleasants noted that the funnel points were north and east of the corn belt, so they would not show the effects of losses in Midwestern farm fields. “Nobody wanted to hear that the monarchs aren’t declining, as crazy as that sounds,” Davis says.

His paper did get the attention of Anurag Agrawal, an evolutionary ecologist at Cornell University who had studied how monarchs use chemicals produced by milkweed. He, too, began to suspect that Pleasants and Oberhauser’s story, while clear and compelling, was too simple to explain the population dynamics of an insect traversing a vast and varied landscape. In Agrawal’s home state of New York, for example, farm fields nestle among meadows, pastures and other ecosystems. It seemed to him that even if milkweed disappeared from crop rows, there would be plenty of other places for monarchs to find the plants.

Not everyone welcomed this perspective, Agrawal says. At a 2012 meeting that Oberhauser hosted at the University of Minnesota, he asked a group of participants what they thought of Davis’s recent paper. Agrawal recalls that Chip Taylor grabbed his arm and asked him not to suggest that a monarch decline might be overstated because it would undermine conservation efforts. “I was in utter disbelief,” Agrawal says. “For somebody to get into your personal space, grab your hand and say, ‘Don’t let me hear you say this’—I’ll never forget it.” Taylor says he does not remember the encounter and doubts it happened.

But there were others who shared Agrawal’s and Davis’s doubts. Leslie Ries, an ecologist at Georgetown University, who was also at that meeting, turned to data from a monitoring program run by the North American Butterfly Association, or NABA. The group recruits volunteers to drive to selected sites and record all the butterflies they see within a 24-kilometer-diameter circle over a single day. Ries reported in a 2015 paper that their data set, as well as a separate one specific to Illinois, showed no evidence that the monarch population in the north had declined over 21 years.

Agrawal went a step further, gathering several long-term tallies of monarch populations at different parts of the life cycle, including the overwintering data, the NABA data and the funnel-point counts. He and several colleagues wanted to see whether population estimates at one stage could predict estimates at the next stage—a chain of connections crucial to the argument that fewer summer milkweed plants in the Midwest led to fewer winter butterflies in Mexico. The scientists reported in 2016 in the journal Oikos and again in 2018 in Science that there was one big gap near the end of this chain: the last end-of-summer counts did not, in fact, predict winter populations. As Ries had found, summer counts stayed roughly constant even when the winter counts fell. Agreeing with Davis, Agrawal and his co-authors suggested that something seemed to be culling monarchs during their southward fall migration, which seemed more important than events during summer breeding.

A different kind of study gave the skeptics further ammunition. In 2017 Tyler Flockhart, a population biologist then at the University of Guelph in Ontario, sought to determine not why monarchs were dying but where they were coming from. He and his colleagues analyzed isotopes of the elements hydrogen and carbon in more than 1,000 monarch butterflies collected in Mexico by Brower and others over four decades. These isotopes are present in varying ratios in different regions and are taken up by the insects’ bodies and wings, forming a kind of geographic signature that indicates where the overwintering butterfly originally fed. Flockhart concluded that the Midwest appeared to be the departure point for only around 38 percent of Mexico-bound monarchs. Monarchs also came in large numbers from the northeastern and southern U.S. and from central and eastern Canada, where corn and soybeans, on a percentage basis, cover far less land.

Different Suspects

To Agrawal and Davis, Flockhart had provided more damning evidence against the milkweed limitation hypothesis. If fewer than two in five monarchs come from the corn belt to begin with, they asked, how could milkweed loss there account for the dramatic losses in Mexico?

Flockhart himself is more cautious. Although there may still be enough total milkweed across North America to support a healthy monarch population, he suspects that the use of Roundup may have shifted the milkweed distribution in ways that could do harm. If the chemical’s effect has been to concentrate milkweed plants in smaller areas outside farm fields, female monarchs may have to lay all their eggs closer to one another, forcing more caterpillars to compete for the same food and stressing the population, he suggests.

Flockhart’s speculation highlights a quandary faced by milkweed contrarians such as Agrawal and Davis. Simply poking holes in the limitation hypothesis was not enough. They needed a different culprit to convince scientists something else was going on, and they did not really have one.

Then, in the spring of 2019, a separate team of researchers found two likely suspects: harm to nectar-producing plants along the migratory route and changes in forest density in Mexico. In a paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, a team led by Elise Zipkin, a quantitative ecologist at Michigan State University, examined statistical correlations among monarch population sizes at different times of the year and a vast array of environmental data. It was the first investigation to divide the winter monarchs into their 19 individual colonies rather than lumping all the forested areas together. Colonies with more dense forest cover, it turned out, hosted more butterflies. “It’s shocking that nobody had done that before,” Zipkin says.

Zipkin’s team also used satellite imagery to quantify the amount of living plant material in a given landscape. When the southern U.S. was greener in the fall, more monarchs arrived in Mexico; when it was browner, as happens during droughts, fewer did. This pattern arose because greener, healthier plants produce more nectar capable of sustaining migrating monarchs, Zipkin and her co-authors suspect. And indeed, a powerful drought hit the southern U.S. between 2010 and 2013, just as the Mexican monarch population was bottoming out.

To Agrawal and Davis, the study pointed to real, nonmilkweed causes of population problems late in the migration. “That’s the paper that addresses it most quantitatively,” Agrawal says. There are also other, more vaguely outlined suspects. Davis thinks a protozoan parasite that infects monarchs could be on the rise. According to research by Davis’s fellow University of Georgia ecologist Sonia Altizer (she and Davis are married), levels of Ophryocystis elektroscirrha, which can weaken or kill monarchs, might be reaching higher levels in insects in the southern U.S. Additionally, Davis and other researchers have suggested that habitat change has increased physiological stress in migrating monarchs, sapping their endurance during the long fall trek.

A New Case

The new evidence could indicate that there may be multiple culprits in the monarch decline, not just one. That perspective has even won over—partly—Oberhauser, the original milkweed-loss proponent. “I was probably being too strong in my argument that there was nothing happening in the migratory range,” says the scientist, now director of the University of Wisconsin–Madison Arboretum. Others have described the monarchs’ plight as “death by a thousand cuts.”

But she still believes milkweed loss is the deepest cut. “I know Andy and Anurag really well. I like both of them a lot,” Oberhauser says. “But I’m sort of tired of this argument” that something other than wipeout of milkweed plants is primarily responsible for the decimation of winter numbers. How could something capable of taking out so many monarchs in transit to Mexico remain hidden, she asks? Only milkweed availability and weather changes strongly affect monarch numbers, according to a computer model she and some colleagues used in a 2017 study.

Oberhauser and Pleasants also contend that summer counts that show no decline—numbers relied on by Agrawal, Ries and Davis—had problems: They were done by volunteers who rarely ventured into farm fields, so they missed steep population drops in those places. Logically, she insists, there have to be summer drop-offs. If monarchs’ winter populations are dwindling to lower and lower numbers year by year, how could the offspring of that shrinking group rebound to the same high summer numbers in many years? “It just makes absolutely no biological sense,” she says.

Zipkin also thinks the milkweed limitation hypothesis remains in play. Along with Oberhauser, she has found evidence in data from Illinois that glyphosate use, in conjunction with changes in springtime weather, can affect local monarch butterfly abundance in summer. “It’s hard for me to believe ... that the amount of milkweed on the landscape is not influencing monarchs.My question is: How much is it doing that?” Zipkin says.

Indeed, that is everyone’s question. To get an answer, scientists have launched a data-gathering effort called the Integrated Monarch Monitoring Program, which aims to do statistically robust counts of monarchs correlated with habitat variables in hundreds of locations across the continental U.S. Program leaders have randomly selected sites and invited both professional and citizen scientists to monitor them and send in data using standardized guidelines so researchers can look for trends. Volunteers have been collecting data since 2017, and there are now 120 people monitoring 235 sites. “We are getting some power, ramping up,” Oberhauser says.

All sides agree that helping the monarch cannot wait until the science is settled. The area of Mexican forest occupied by monarchs plummeted in 2013 to a spot barely larger than a standard soccer pitch, a record low. Although the migratory population has rebounded somewhat since then, most researchers still view its status as precarious. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service says it will rule on the endangered species petition later this year.

To improve butterfly-habitat regions in general, Oberhauser would like to see the U.S. Department of Agriculture increase the hectares in its Conservation Reserve Program—the most important federal program supporting wildlife areas on farmland—which has dropped to below 9.3 million from a 2007 high of almost 15 million.

Conservation measures are also needed to better protect the Mexican forests, researchers say. Even though the core forest area is officially protected—it is a United Nations World Heritage Site—logging continues on the periphery, where butterflies also spend time, and illegal avocado plantations have made incursions. A warming climate could make the reserve inhospitable to the monarch-nurturing fir trees, which require lower temperatures. Already an effort is underway to plant these trees in higher and cooler areas on the mountain slopes.

The monarch butterfly has been many things to many people: an obsession for gardeners and naturalists, a touchstone for conservationists, an international goodwill ambassador for politicians and, for much of the public, a vessel for anxieties about humans’ increasing impact on the planet. For scientists, the monarch migration began as a mystery in the 1800s, and its solution in the following century established the butterfly as a wonder of the natural world. Now the butterfly is at the center of yet another puzzle. This time its fate may depend on the answer.