Back in 2010, we celebrated the life of Martin Gardner, who died that year at the age of 95. He wrote the Mathematical Games column for Scientific American magazine for nearly 25 years, and he remains the gold standard for this publication's columnists.

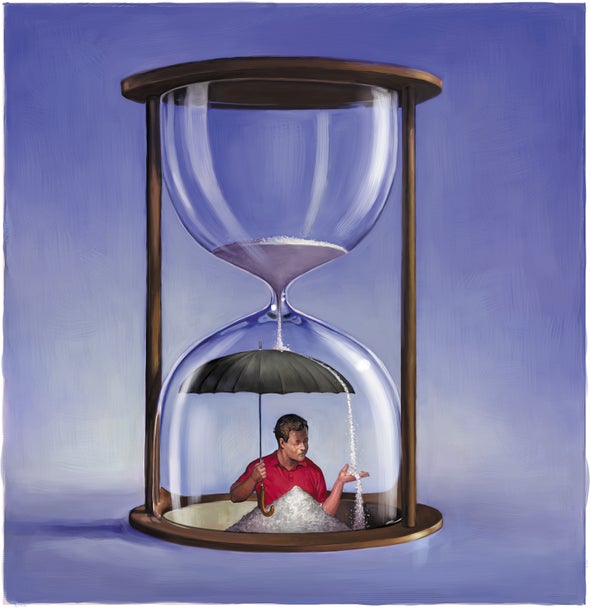

Upon Gardner's death, I interviewed his friend and protégé Douglas Hofstadter, the Pulitzer Prize–winning author of Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid. The book came out in 1979, when Hofstadter was 34. Which meant that in 2010 he was 65. And it struck me that it should take much longer to go from 34 to 65 than a mere 31 years. It really should take more like 50 years to go from being 34 to 65, I thought, even though the arithmetic regarding that transition was inarguably ironclad.

In a somewhat related vein, this issue of Scientific American marks 25 years since the first appearance of Anti Gravity. In 1995 I was 37 years old and in my salad days, when I was green in judgment. And in only 25 years I've turned into an alte kaker. I'm still green, but now it's because of digestive issues.

Horror movie maven David Cronenberg captured the weirdness of this fast-forwarding in the introduction to a 2014 English translation of Franz Kafka's The Metamorphosis: “I woke up one morning recently to discover that I was a seventy-year-old man. Is this different from what happens to Gregor Samsa in The Metamorphosis? He wakes up to find that he's become a near-human-sized beetle.... Our reactions, mine and Gregor's, are very similar. We are confused and bemused, and think that it's a momentary delusion.... These two scenarios, mine and Gregor's, seem so different, one might ask why I even bother to compare them. The source of the transformations is the same, I argue: we have both awakened to a forced awareness of what we really are, and that awareness is profound and irreversible; in each case, the delusion soon proves to be a new, mandatory reality, and life does not continue as it did.”

The previous more than 300 words of throat clearing is to set up the announcement that I'm hanging up my spikes. Well, in truth I hung up the spikes a very long time ago, when other kids my age started throwing breaking pitches. So let's say I'm hanging up my keyboard.

I'll still be making bad puns and snide remarks, of course, and I'll be ranting about antiscience politicians, but it'll mostly be just for the benefit, if you can call it that, of my wife and cats. Although it's not impossible that I may return to these pages from time to time when said wife and cats inform me that I really should share my golden nuggets of insight with a wider audience if that will get me out of the living room.

By the way, I'd be remiss if I didn't note that the greatest commentary on The Metamorphosis occurs in Mel Brooks's 1967 movie The Producers, when the title characters are looking for the worst play in the world in order to guarantee a flop so they can keep most of the million dollars they raise rather than spend it on the production. Max Bialystock, brilliantly played by Zero Mostel, opens one of the hundreds of manuscripts around him and says, “‘Gregor Samsa awoke one morning to discover that he had been transformed into a giant cockroach.’ It's too good.” Which in fact it was.

Back to Cronenberg and his “mandatory reality.” In 2002 a White House official scoffed at journalist Ron Suskind for being in “the reality-based community.” The official explained, according to Suskind, “We're an empire now, and when we act, we create our own reality.”

I had two responses to that anecdote and attitude then that I hold to today, as the current White House's relationship with reality seems literally psychotic. First, Scientific American is the voice of the reality-based community. Second, if you think you create your own reality, real reality will come back to bite you in the ass.