As coronavirus cases reach new peaks, surpassing 200,000 cases a day in the United States, public health departments are overwhelmed. Departments are racing to hire yet more contact tracers and some are even asking people to do their own contact tracing and notification. Other states are just now pushing out big tech’s solution to the pandemic: mobile contact tracing apps.

Initially, the hope was that contact tracing apps would be a silver bullet for contact tracing. Evidence shows this is not the case. Many European countries have been using these apps for months with limited success.

As a result, some public health departments are taking matters into their own hands, turning away from big tech and innovating their own technology solutions. Early evidence suggests these solutions may work better both for public health and for the public.

Traditional contact tracing works by interviewing those infected with COVID-19 about whom they have encountered during the prior two weeks. The contact tracers then contact those who have been exposed to notify them of exposure. But the relationship does not end there.

Contact tracers ask those who have been exposed to monitor their symptoms, for example, by taking their temperature twice per day. They call back frequently to collect symptom data and ensure that those who become ill get appropriate care and avoid infecting others. Contact tracers seek to build trust with those they are in contact with, to encourage truthful and accurate reporting from those they contact.

Before the pandemic hit, the U.S. employed about 2,200 contact tracers. The American Medical Association estimates that more than 100,000 contact tracers are needed to address the pandemic.

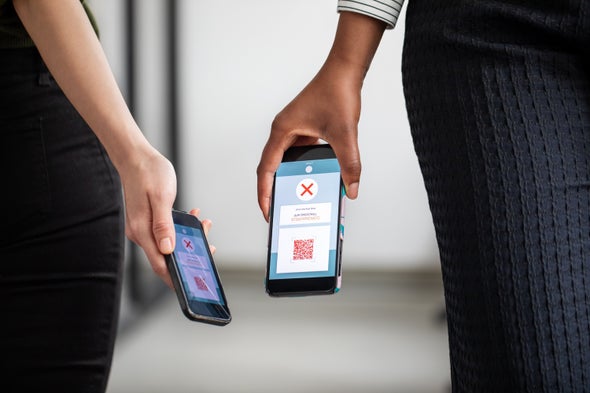

Contact tracing apps aim to fill this gap by automating the contact tracing process. The apps track when app users encounter each other. If a user later uploads a positive coronavirus test result, app users who’ve been exposed can be notified, all through the app.

But, contact tracing apps have struggled with low adoption rates, issues with the accuracy of the Bluetooth technology on which the apps rely to detect when app users come into contact with each other, and ensuring that app users remember to bring their phones with them and to upload their coronavirus test results.

These struggles have arisen, in part, because of how and why contact tracing apps were created. Contact tracing apps were imagined and developed by technology companies with little input from public health experts or the public the apps are designed to serve.

When tech companies impose technologies in domains they do not understand, they often fail. Consider the massive open online courses that technologists once dreamed would replace traditional degree programs or Google Health, intended to solve the issue of medical records sharing from the patient perspective.

Faced with this new surge, some public health departments have started building their own solutions. They are leveraging their experience with contact tracing and the technology they already have in order to scale contact tracing efforts.

For example, in Michigan, Ottawa County's public health department automated contact tracing symptom checks and follow-ups by repurposing their existing OnBase case management software and online survey tools

Ottawa contact tracers make first contact with at-risk individuals the traditional way: with a phone call from a trained contact tracer who can collect the necessary information and establish a relationship.

Follow-ups for symptoms, however, are done by sending a simple two-question survey via text message to those who have been exposed and added to the contact tracing database. Public health data analysts can analyze symptom data to determine when a citizen needs additional phone-based or medical-care follow-ups.

In stark contrast to contact tracing apps that have at best achieved 35 percent adoption, over 91 percent of those who receive symptom-check text messages from Ottawa’s system complete their surveys. At least 10 other public health departments have now adopted Ottawa’s system through partnering with ImageSoft, the tech company that powers Ottawa’s system.

This approach, blending technology with manual contact tracing, solves two key problems with contact tracing apps: trust and efficacy. Trust is a key foundation of public health and a big problem for contact tracing apps; my own research shows that people are divided on whom they trust to provide the apps as well as whether they trust the apps to actually work and to protect their data.

Beyond building trust, human contact tracers are also far more effective than apps.

Contact tracers attempt to reach all citizens who have been exposed repeatedly—at multiple times a day, multiple days a week—until they make contact. In contrast, contact tracing apps rely heavily on people acting, unprompted.

For the apps to work, people need to voluntarily download the app, carry their phone with them when they leave the house, and upload their test results. This full reliance on citizens to not just comply with contact tracing, but to participate actively, risks leaving significant gaps in protection, especially if only a minority of the population adopts these apps, let alone properly uses them.

If contact tracing apps continue to fall short on adoption as the surge of cases increases, now is perhaps the time for big tech to remember that they need to listen to the public health experts these apps attempt to replace, and the public that has failed to adopt this new technology.

Rather than relying on inferring people’s wants and needs from their data, tech companies need to engage those they serve directly and solicit the expertise they do not have. By partnering with public health departments and letting experts drive the innovation, tech companies can help keep contact tracers afloat rather than imposing solutions headed toward failure.