Today, conversations around abortion in modern Christianity tend to take as a given the longstanding moral, religious and legal prohibition of the practice. Stereotypes of medical knowledge in the ancient and medieval worlds sustain the misguided notion that abortive and contraceptive pharmaceuticals and surgeries could not have existed in the premodern past.

This could not be further from the truth.

While official legal and religious opinions condemned the practice, often citing the health of women, a wealth of medical treatises produced by and for wealthy Christian women across the Middle Ages betray a radically different history—one in which women had a host of pharmaceutical contraceptives, various practices for inducing miscarriages, and surgical procedures for the termination of pregnancies. When it came to saving a woman’s life, Christian physicians unhesitatingly recommended these procedures.

Since antiquity, the termination of pregnancies has long been associated with women at the margins of society, such as sex workers, and highlighted not only for the termination of the fetus’s life, but for the great danger it posed to women. For instance, in the Hippocratic Oath, Hippocrates refuses to assist in or recommend euthanasia and additionally refuses to give women abortifacients given the danger to which they put the life of the mother.

Religiously, the Church Council of Ancyra in 314 A.D. stated that women found to have committed or attempted an abortion on themselves or others were to be exiled from the Church for 10 years, revising earlier suggestions that they be exiled for life. Yet, in the mid-fourth century, the Church Father Basil the Great revises these decrees, suggesting that time should not be proscriptive but dependent on the repentance of the person. There, however, he focuses not just on the fetus, but again on the danger of these procedures for women, who “usually die from such attempts.”

The laws of the early Christian world generally reflected these prohibitions, outlining exile as the punishment for whomever has undertaken an abortion or aided in one—or, death if the person dies in the process. Many of these laws were codified in the sixth-century Digest of Justinian, a legal compendium culled from ancient legislative opinions.

Nevertheless, these legal opinions betray the real complexity that abortions had in the ancient and medieval worlds. For example, the Digest cites the opinion of the jurist Tryphonius, where a woman was sentenced to death for undertaking an abortion, precisely because she did so with the malicious intent of denying her husband an heir by aborting the unborn inheritor. Legally, we see abortions being intimately associated with a patriarchal control of lineage and reproduction. The Digest clarifies that if a woman undertakes an abortion after a divorce, “so as to avoid giving a son to her husband who is now hateful,” however, she should only be temporarily exiled.

The fourth-century Church Father John Chrysostom even turned these stereotypes on their head. Though criticizing abortions, in one sermon he offers the example of a sex worker forced to have an abortion so as to not lose her livelihood. While damning the act as a murderous practice, he places blame not on the woman, but on her client, chastising the man by saying that the sex worker cannot be criticized for seeking out an abortion, writing, that while “the shameless act is hers, the cause of it is yours.” Thus, it is the sex worker’s client who is the cause of the murder, not she who requires her attractive body to survive.

Despite the prohibition in the Hippocratic Oath, gynecological texts were replete with recipes for contraceptive and abortive suppositories. The second-century gynecology of Soranus of Ephesus details these recipes and advocates their use for women who have a medical reason to prevent pregnancy, strongly opposing their use simply “because of adultery or out of a consideration for youthful beauty,” given the health risks involved. Thus, adultery and a conceited desire to preserve one’s good looks were often lodged against women known to practice abortions.

The recipes of Soranus were transmitted across the centuries in various texts, each demonstrating an active history of use and commentary. For example, in Aëtius of Amida’s sixth-century medical treatise, the author details the use of contraceptive vaginal suppositories, elaborating on the improvements to the recipe from Soranus’s time. There, Aëtius writes that once the contraceptive has been used, “if she wishes, [the woman] may have intercourse with a man. It is infallible because of its many trials.”

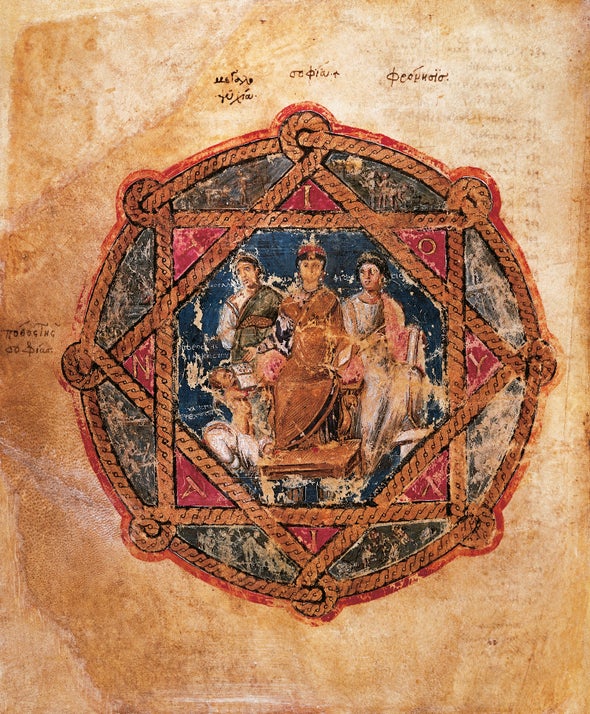

Aëtius’s gynecological treatise has often been associated with the patronage of the elite imperial circle of Empress Theodora in Constantinople, an empress whom the court historian Procopius once described as often conceiving, “but by using almost all known techniques she could induce immediate miscarriage.” The use and efficacy of contraceptives and abortifacients extend throughout the Christian Middle Ages. In one 12th-century text from Salerno, the author offers the example of sex workers, who frequently have intercourse yet only rarely conceive.

Therefore, the medical historical evidence proposes a very different story from that told by official religious or legal texts. The fact of the matter is that good Christian women were indeed undertaking abortions and using contraceptives. Yet, wealthy and elite Christian women had not only recourse to the best medical knowledge of their era but also the privacy to undertake these practices without shame.

Most surprisingly, however, these medical practices were not only relegated to herbal, pharmaceutical contraceptives and abortifacient drugs, but also the various surgical interventions, what today we would refer to as a late-term abortion.

In the early 10th-century Life of Patriarch Ignatios, by Nicetas David Paphlagon, a narrative of a religious figure, the author recounts the story of a woman in labor with a breeched birth. There, she is in immense pain and the author writes that “in order to prevent the woman too from perishing with her child, the doctors [attended] to operate on the baby and draw it out by cutting it limb by limb.” While the procedure ultimately does not need to happen thanks to the miraculous workings of a relic, the author, without any moralization or shame, details here the contemporaneous procedures for an embryotomy, as described in medieval surgical manuals.

Further corroborating the continued use of this surgery, we can note that the sixth-century text by Aëtius of Amida (citing a certain Philumenos and Soranus), details the operation for an embryotomy similarly. The same operation is also recounted perfectly in Paul of Aegina’s own seventh-century compendium on surgical practices.

These late-term abortions echo their modern counterpart, demonstrating that this was a known and established practice in the Middle Ages. This medical knowledge flourished in particular in the Greek-speaking, eastern Roman Empire, most commonly known to us today as the Byzantine Empire. Glimmers of the medical prowess of the Byzantine Empire and its long-thriving history are scattered across medieval sources.

In fact, one of the first recorded uses of a Caesarian section on a living woman comes down to us from Visigothic Spain, but the text tells us the deed was performed by a skilled “Greek” (aka Byzantine) doctor, who is called to save the life of a living mother whose child has died in the womb.

While Caesarians were used in antiquity, they were deployed then only to rescue a child from a dead mother. In the Lives of the Fathers of Mérida, composed in the 630s, the author chronicles the life of Paul, bishop of Mérida around 540/550. Paul is a Greek who had trained as a doctor in his youth. In order to save the life of a wealthy woman, he must put his clerical garments aside and sully his hands with an embryotomy. The text describes how “with wonderous skill he made a most skillful incision by his cunning use of a knife and extracted the already decaying body of the infant, limb by limb, piece by piece,” in order to save the woman’s life.

The only difference between the figure of the sex worker shamed for her abortions and the persons for whom these gynecological and surgical books were commissioned is that the latter were courtly elites. Therefore, they had better recourses to medical knowledge, treatment and privacy.

But, the fact that stories of late-term abortions even find their way into saints’ lives without judgment belie a more important fact: that abortions undertaken for the preservation of a woman’s life or health were rarely, if ever, under attack by medieval Christian authors. Not even the moralizing religious texts touch upon such cases. This is a fact that modern Christian pundits have not merely forgotten, but just never learned.