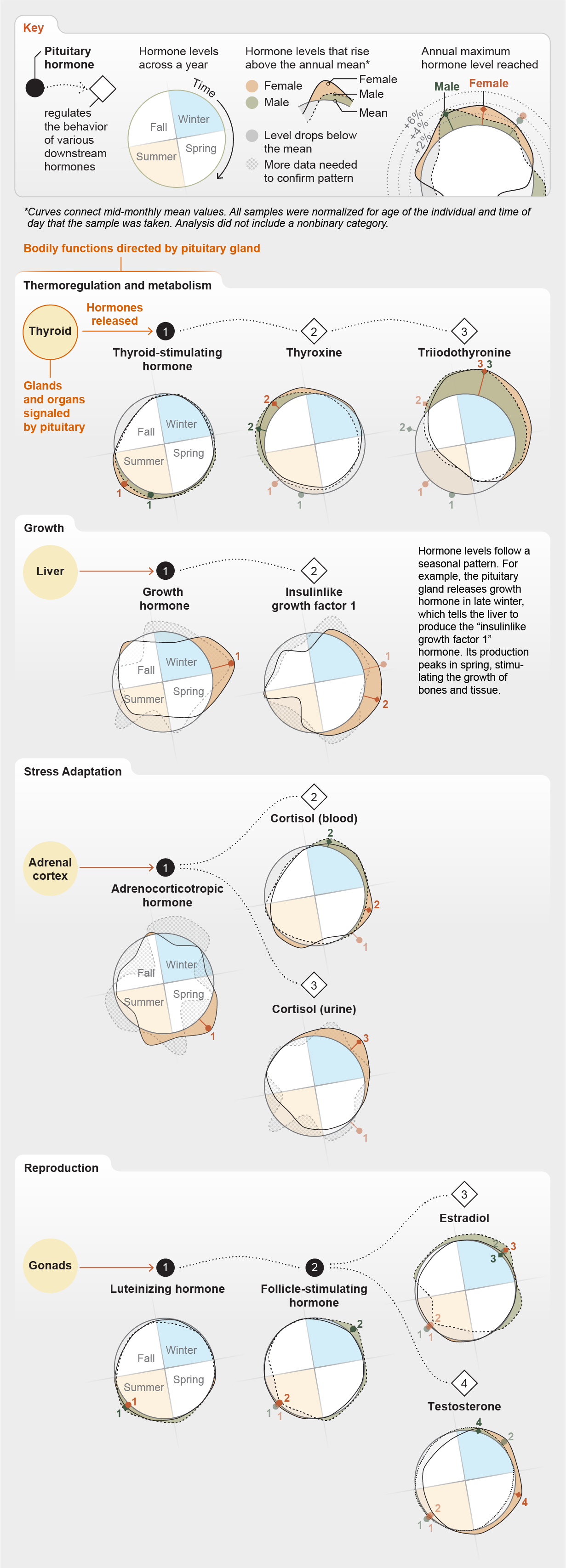

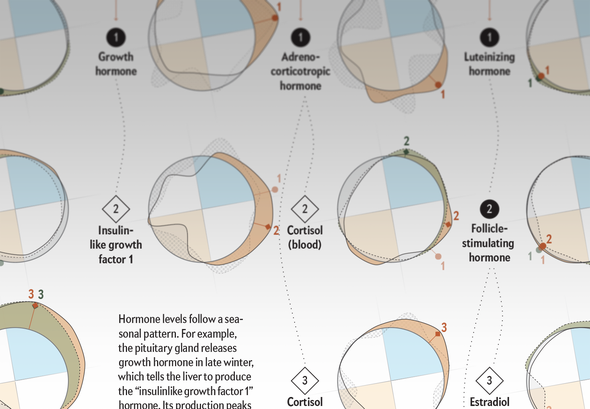

Hormones can surge and drop within minutes to direct many of our daily functions: sleep, digestion, reactions to stress. General hormone levels rise and fall slightly across the year as well. New work shows that the pattern has a seasonal memory of sorts, too, governed by a newly discovered internal clock. By studying millions of blood tests, researchers at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot, Israel, found that hormone-producing glands grow and shrink in continuous, self-regulating annual cycles. Each maximum or minimum causes hormone levels to rise or fall by several percent—small but significant—though often several months later. The cycles, and lag times, are evident in hormones released by the thyroid, liver, adrenal cortex and gonads, directed by the pituitary gland in the brain. The results support a growing body of work that shows that fertility tends to be higher in midwinter, kids grow faster in spring and moodiness peaks in winter.