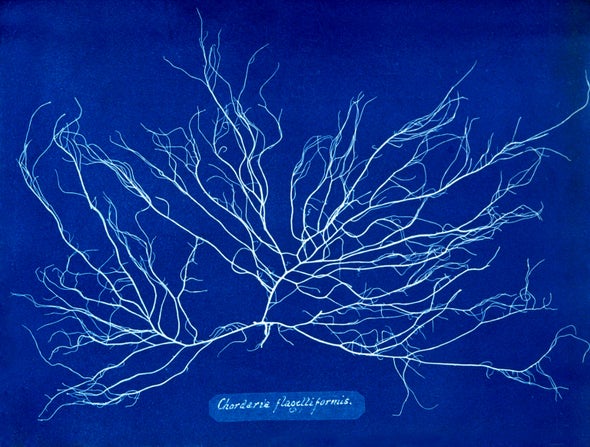

Born in England in 1799, Anna Atkins was an amateur botanist (an activity then considered by British society to be an appropriate occupation for a lady). She collected and drew by hand samples of the myriad varieties of algae found along British coastlines. As Atkins told a friend, however, some specimens were so small and detailed in places that she had no choice but to experiment with an alternative and brand-new documentation technique.

In the mid-1840s, English astronomer and chemist John Herschel introduced Atkins to his new photography method. When he coated a piece of paper in iron salts and left it to sit out in the sun, the light would turn the page blue—save for any portion covered by the object sitting on top. Herschel called the technique cyanotyping, but it is better known today as blueprinting.

Atkins adopted this method with her alga samples, bending the photosynthetic organisms, which were becoming increasingly brittle from time out of the water, on each page so that the chemicals and the sun would form a lasting impression of her collections. The pioneering botanist put her cyanotypes of algae in three volumes of Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions, of which only around a dozen copies are known to still exist. The first volume, released in October 1843, is considered to be the earliest book of photography ever published.

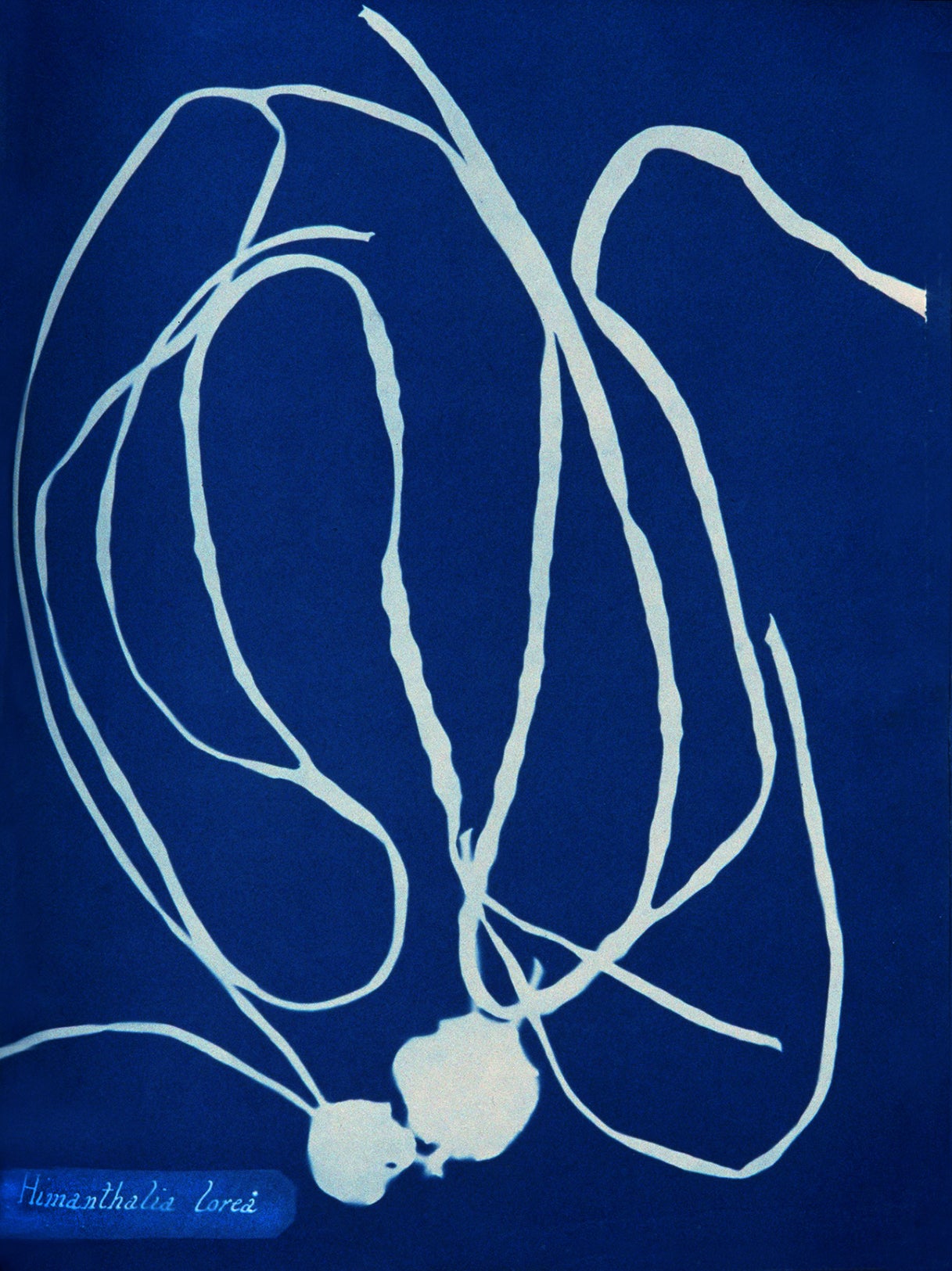

Himanthalia lorea. A close relative of this brown seaweed, Himanthalia elongata, might show up in your grocery store as “sea spaghetti.” Though people have harvested the pasta impostor from French, Spanish and Portuguese shorelines for centuries, warming waters might be reducing population size.

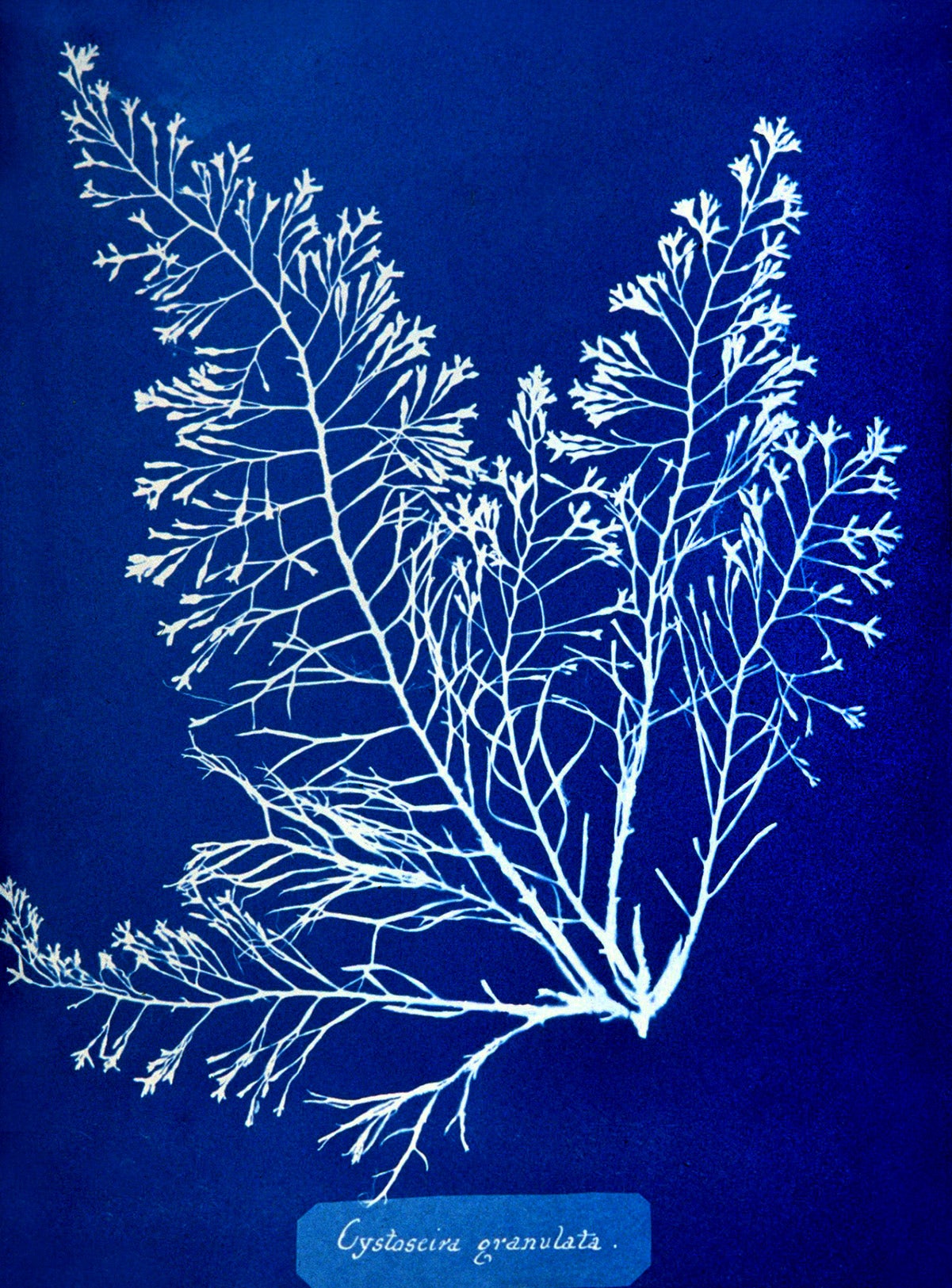

Cystoseira granulata. This species and some of its closest relatives sprout into dense aquatic forests along coasts. Fewer of these specimens exist to be collected than when Atkins was around. Biologists suspect pollution, too much nutrient runoff and increasingly dirty waters are killing off this genus of seaweed.

Halymenia ligulata var. latifolia. This particular photograph also documents the incremental nature of the scientific method: DNA analysis has shown that people mistakenly lumped at least three alga species under the name Halymenia latifolia since that label was created.

Anna Atkins, 1861.

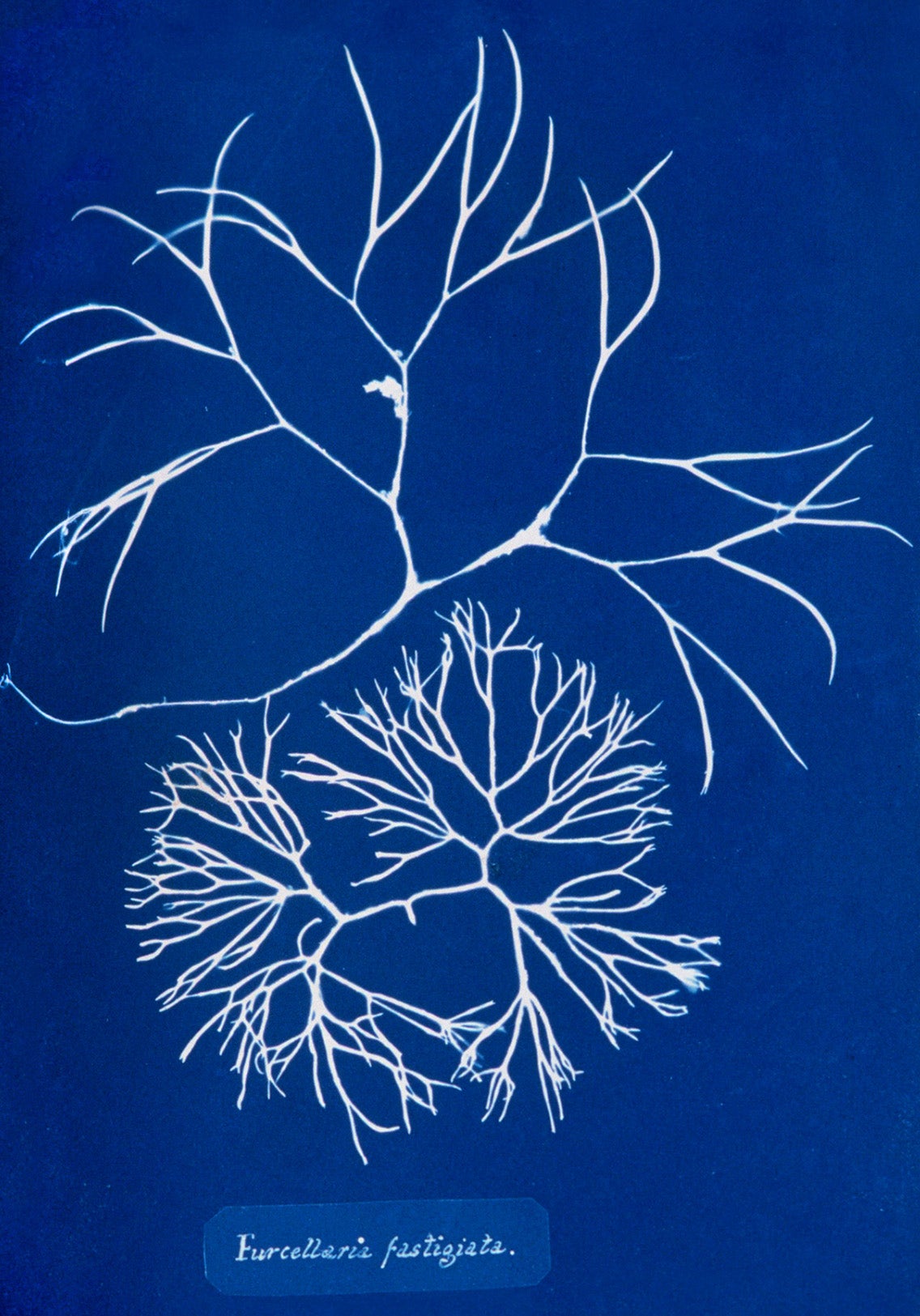

Furcellaria fastigiata. Like other red algae, this species generates sugars that scientists coax into food-thickening gels. Goops from Fucellaria specifically are known as Danish agar.

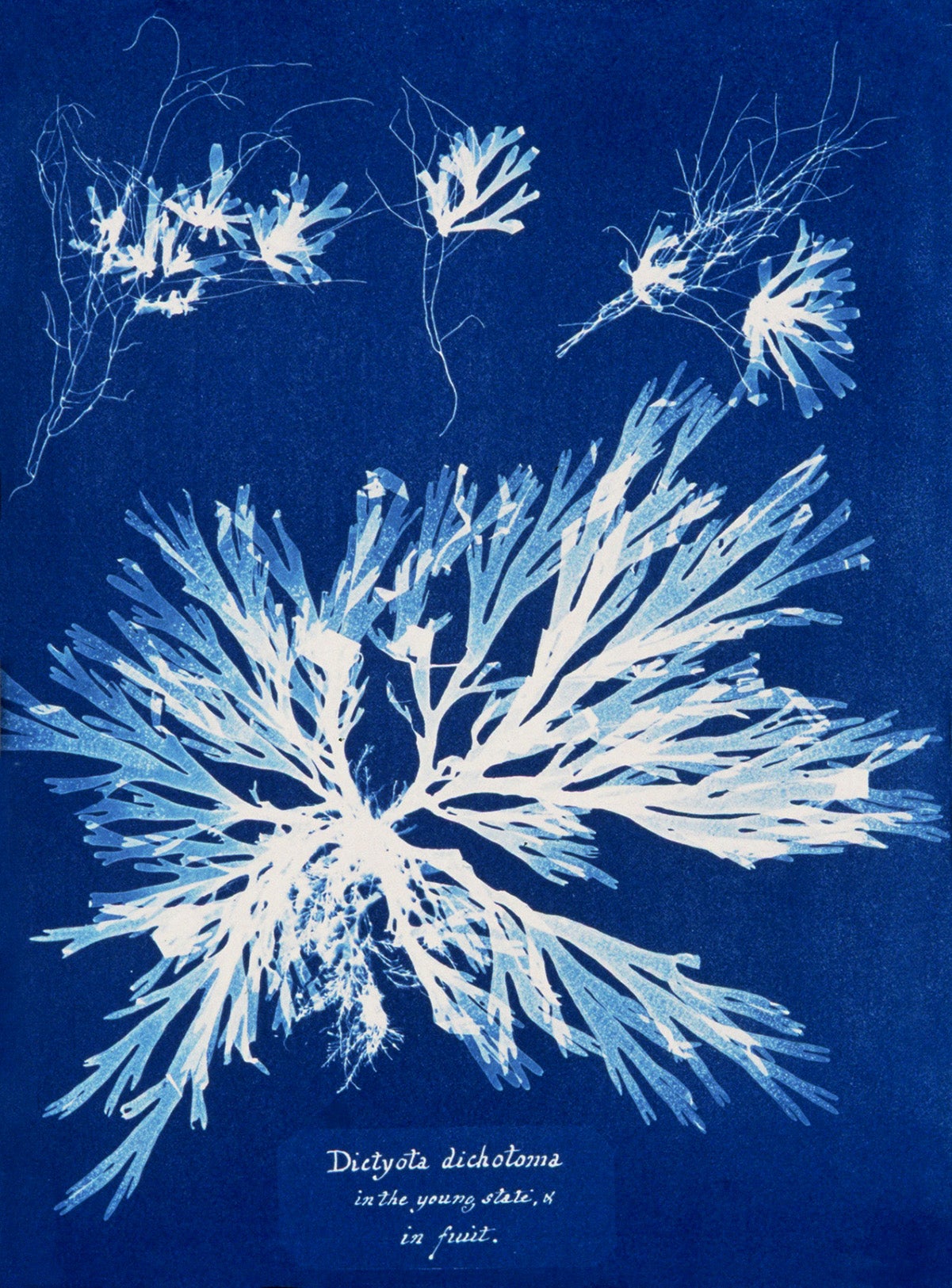

Dictyota dichotoma in its young state and in fruit. The Dictyota genus of brown seaweed has proved itself as a potential feed additive for cows that might cut back on the greenhouse gas methane they release from flatulence and burping.

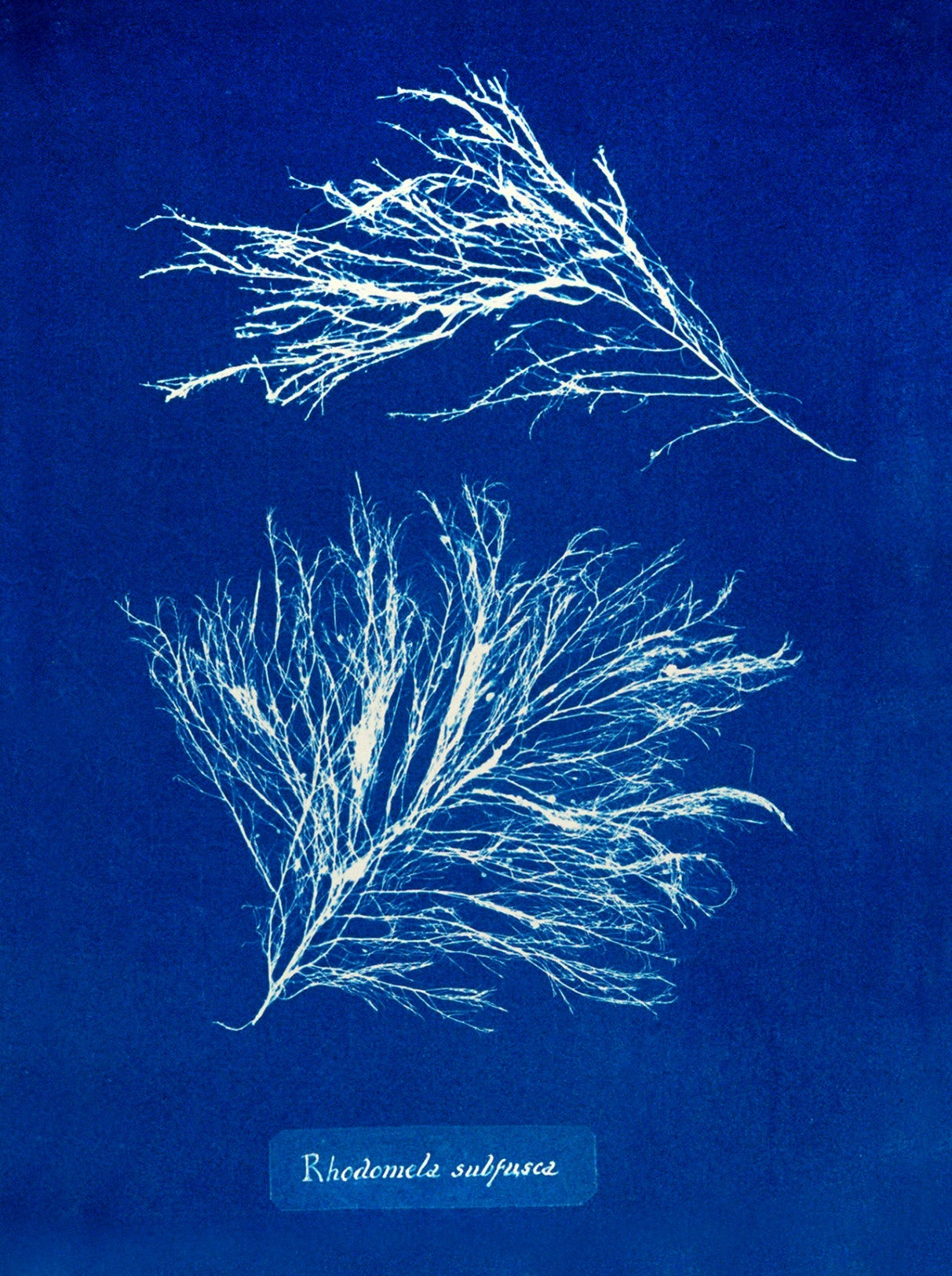

Rhodomela subfusca, a red alga. Scientists devote time and money to algae because the photosynthesizers are generally stuck in place while coping with shifting temperatures, salt levels and nutrient availability. To thrive, algae likely develop unique compounds—molecules that are probably found nowhere else—which may be of interest to science and industry.

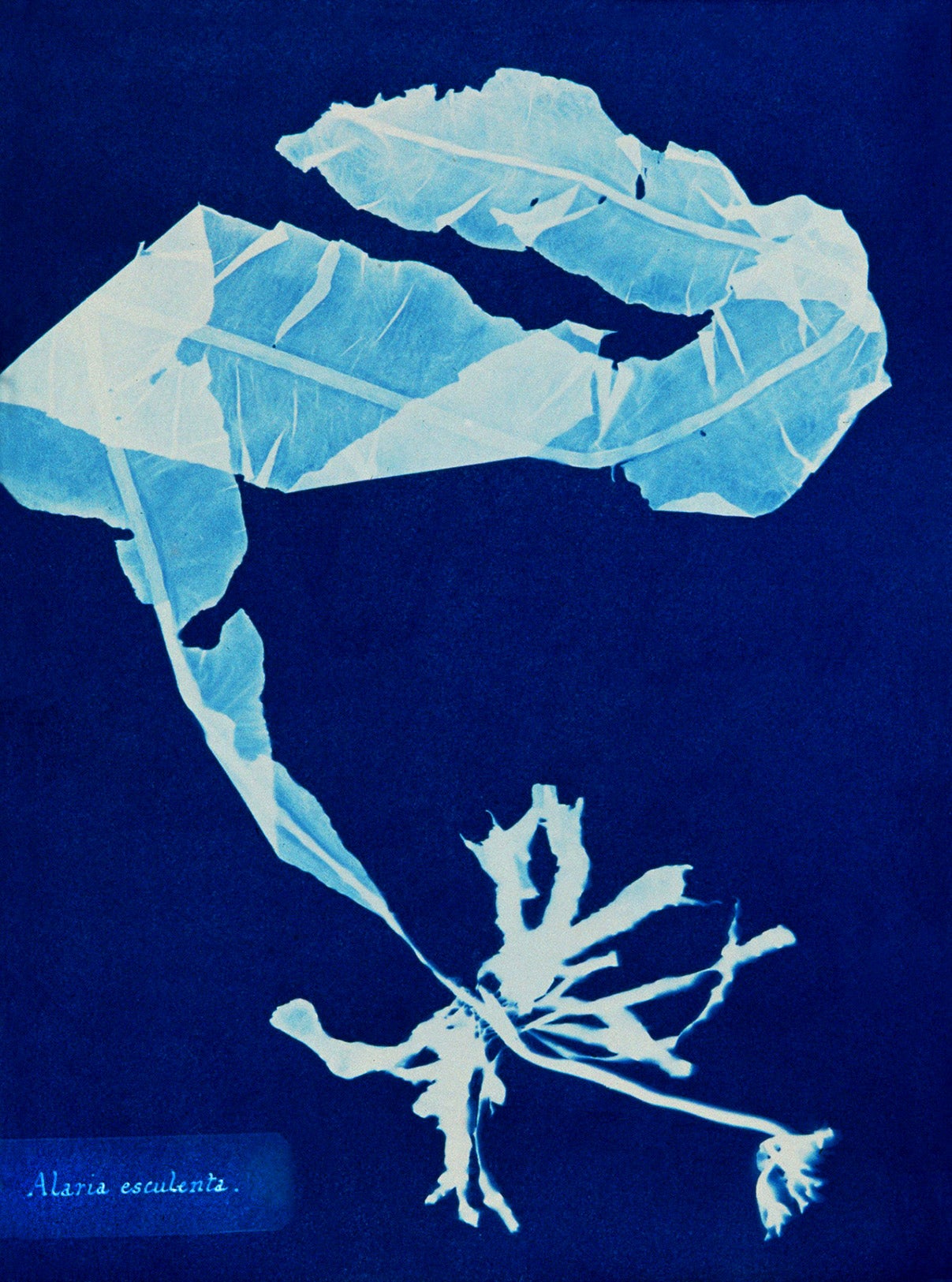

Alaria esculenta. Otherwise known as badderlocks, dabberlocks or winged kelp, this ribbon of an alga variety is popular with seaweed farmers in Maine, where it was one of the first three species to be grown commercially in the U.S.

A version of this article with the title “Science in Images” was adapted for inclusion in the June 2021 issue of Scientific American.