At the start of the 20th century scientists had little knowledge of the building blocks that form our physical world. By the end of the century they had discovered not just all the elements that are the basis of all observed matter but a slew of even more fundamental particles that make up our cosmos, our planet and ourselves. The tool responsible for this revolution was the particle accelerator.

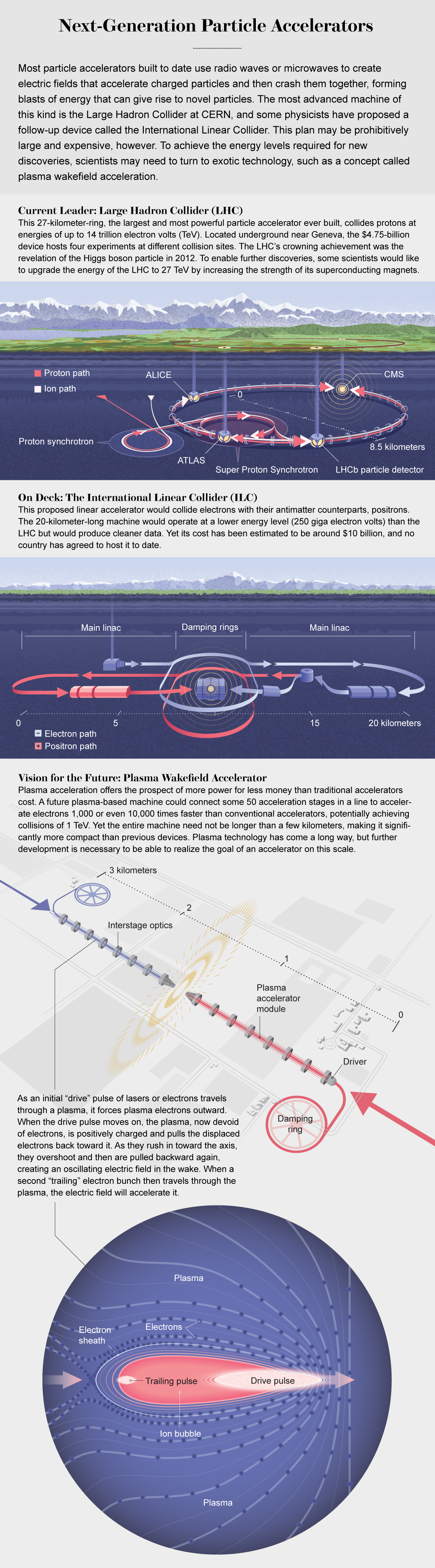

The pinnacle achievement of particle accelerators came in 2012, when the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) uncovered the long-sought Higgs boson particle. The LHC is a 27-kilometer accelerating ring that collides two beams of protons with seven trillion electron volts (TeV) of energy each at CERN near Geneva. It is the biggest, most complex and arguably the most expensive scientific device ever built. The Higgs boson was the latest piece in the reigning theory of particle physics called the Standard Model. Yet in the almost 10 years since that discovery, no additional particles have emerged from this machine or any other accelerator.

Have we found all the particles there are to find? Doubtful. The Standard Model of particle physics does not account for dark matter—particles that are plentiful yet invisible in the universe. A popular extension of the Standard Model called supersymmetry predicts many more particles out there than the ones we know about. And physicists have other profound unanswered questions such as: Are there extra dimensions of space? And why is there a great matter-antimatter imbalance in the observable universe? To solve these riddles, we will likely need a particle collider more powerful than those we have today.

Many scientists support a plan to build the International Linear Collider (ILC), a straight-line-shaped accelerator that will produce collision energies of 250 billion (giga) electron volts (GeV). Though not as powerful as the LHC, the ILC would collide electrons with their antimatter counterparts, positrons—both fundamental particles that are expected to produce much cleaner data than the proton-proton collisions in the LHC. Unfortunately, the design of the ILC calls for a facility about 20 kilometers long and is expected to cost more than $10 billion—a price so high that no country has so far committed to host it.

In the meantime, there are plans to upgrade the energy of the LHC to 27 TeV in the existing tunnel by increasing the strength of the superconducting magnets used to bend the protons. Beyond that, CERN is proposing a 100-kilometer-circumference electron-positron and proton-proton collider called the Future Circular Collider. Such a machine could reach the unprecedented energy of 100 TeV in proton-proton collisions. Yet the cost of this project will likely match or surpass the ILC. Even if it is built, work on it cannot begin until the LHC stops operation after 2035.

But these gargantuan and costly machines are not the only options. Since the 1980s physicists have been developing alternative concepts for colliders. Among them is one known as a plasma-based accelerator, which shows great promise for delivering a TeV-scale collider that may be more compact and much cheaper than machines based on the present technology.

The Particle Zoo

The story of particle accelerators began in 1897 at the Cavendish physics laboratory at the University of Cambridge. There J. J. Thomson created the earliest version of a particle accelerator using a tabletop cathode-ray tube like the ones used in most television sets before flat screens. He discovered a negatively charged particle—the electron.

Soon physicists identified the other two atomic ingredients—protons and neutrons—using radioactive particles as projectiles to bombard atoms. And in the 1930s came the first circular particle accelerator—a palm-size device invented by Ernest Lawrence called the cyclotron, which could accelerate protons to about 80 kilovolts. Thereafter accelerator technology evolved rapidly, and scientists were able to increase the energy of accelerated charged particles to probe the atomic nucleus. These advances led to the discovery of a zoo of hundreds of subnuclear particles, launching the era of accelerator-based high-energy physics. As the energy of accelerator beams rapidly increased in the final quarter of the past century, the zoo particles were shown to be built from just 17 fundamental particles predicted by the Standard Model. All of these, except the Higgs boson, had been discovered in accelerator experiments by the late 1990s. The Higgs’s eventual appearance at the LHC made the Standard Model the crowning achievement of modern particle physics.

Aside from being some of the most successful instruments of scientific discovery in history, accelerators have found a multitude of applications in medicine and in our daily lives. They are used in CT scanners, for x-rays of bones and for radiotherapy of malignant tumors. They are vital in food sterilization and for generating radioactive isotopes for myriad medical tests and treatments. They are the basis of x-ray free-electron lasers, which are being used by thousands of scientists and engineers to do cutting-edge research in physical, life and biological sciences.

Accelerator Basics

Accelerators come in two shapes: circular (synchrotron) or linear (linac). All are powered by radio waves or microwaves that can accelerate particles to near light speed. At the LHC, for instance, two proton beams running in opposite directions repeatedly pass through sections of so-called radio-frequency cavities spaced along the ring. Radio waves inside these cavities create electric fields that oscillate between positive and negative to ensure that the positively charged protons always feel a pull forward. This pull speeds up the protons and transfers energy to them. Once the particles have gained enough energy, magnetic lenses focus the proton beams to several very precise collision points along the ring. When they crash, they produce extremely high energy densities, leading to the birth of new, higher-mass particles.

When charged particles are bent in a circle, however, they emit “synchrotron radiation.” For any given radius of the ring, this energy loss is far less for heavier particles such as protons, which is why the LHC is a proton collider. But for electrons the loss is too great, particularly as their energy increases, so future accelerators that aim to collide electrons and positrons must either be linear colliders or have very large radii that minimize the curvature and thus the radiation the electrons emit.

The size of an accelerator complex for a given beam energy ultimately depends on how much radio-frequency power can be pumped into the accelerating structure before the structure suffers electrical breakdown. Traditional accelerators have used copper to build this accelerating structure, and the breakdown threshold has meant that the maximum energy that can be added per meter is between 20 million and 50 million electron volts (MeV). Accelerator scientists have experimented with new types of accelerating structures that work at higher frequencies, thereby increasing the electrical breakdown threshold. They have also been working on improving the strength of the accelerating fields within superconducting cavities that are now routinely used in both synchrotrons and linacs. These advances are important and will almost certainly be implemented before any paradigm-changing concepts disrupt the highly successful conventional accelerator technologies.

Eventually other strategies may be necessary. In 1982 the U.S. Department of Energy’s program on high-energy physics started a modest initiative to investigate entirely new ways to accelerate charged particles. This program generated many ideas; three among them look particularly promising.

The first is called two-beam acceleration. This scheme uses a relatively cheap but very high-charge electron pulse to create high-frequency radiation in a cavity and then transfers this radiation to a second cavity to accelerate a secondary electron pulse. This concept is being tested at CERN on a machine called the Compact Linear Collider (CLIC).

Another idea is to collide muons, which are much heavier cousins to electrons. Their larger mass means they can be accelerated in a circle without losing as much energy to synchrotron radiation as electrons do. The downside is that muons are unstable particles, with a lifetime of two millionths of a second. They are produced during the decay of particles called pions, which themselves must be produced by colliding an intense proton beam with a special target. No one has ever built a muon accelerator, but there are die-hard proponents of the idea among accelerator scientists.

Finally, there is plasma-based acceleration. The notion originated in the 1970s with John M. Dawson of the University of California, Los Angeles, who proposed using a plasma wake produced by an intense laser pulse or a bunch of electrons to accelerate a second bunch of particles 1,000 or even 10,000 times faster than conventional accelerators can. This concept came to be known as the plasma wakefield accelerator. It generated a lot of excitement by raising the prospect of miniaturizing these gigantic machines, much like the integrated circuit miniaturized electronics starting in the 1960s.

The Fourth State of Matter

Most people are familiar with three states of matter: solid, liquid and gas. Plasma is often called the fourth state of matter. Though relatively uncommon in our everyday experience, it is the most common state of matter in our universe. By some estimates more than 99 percent of all visible matter in the cosmos is in the plasma state—stars, for instance, are made of plasma. A plasma is basically an ionized gas with equal densities of electrons and ions. Scientists can easily form plasma in laboratories by passing electricity through a gas as in a common fluorescent tube.

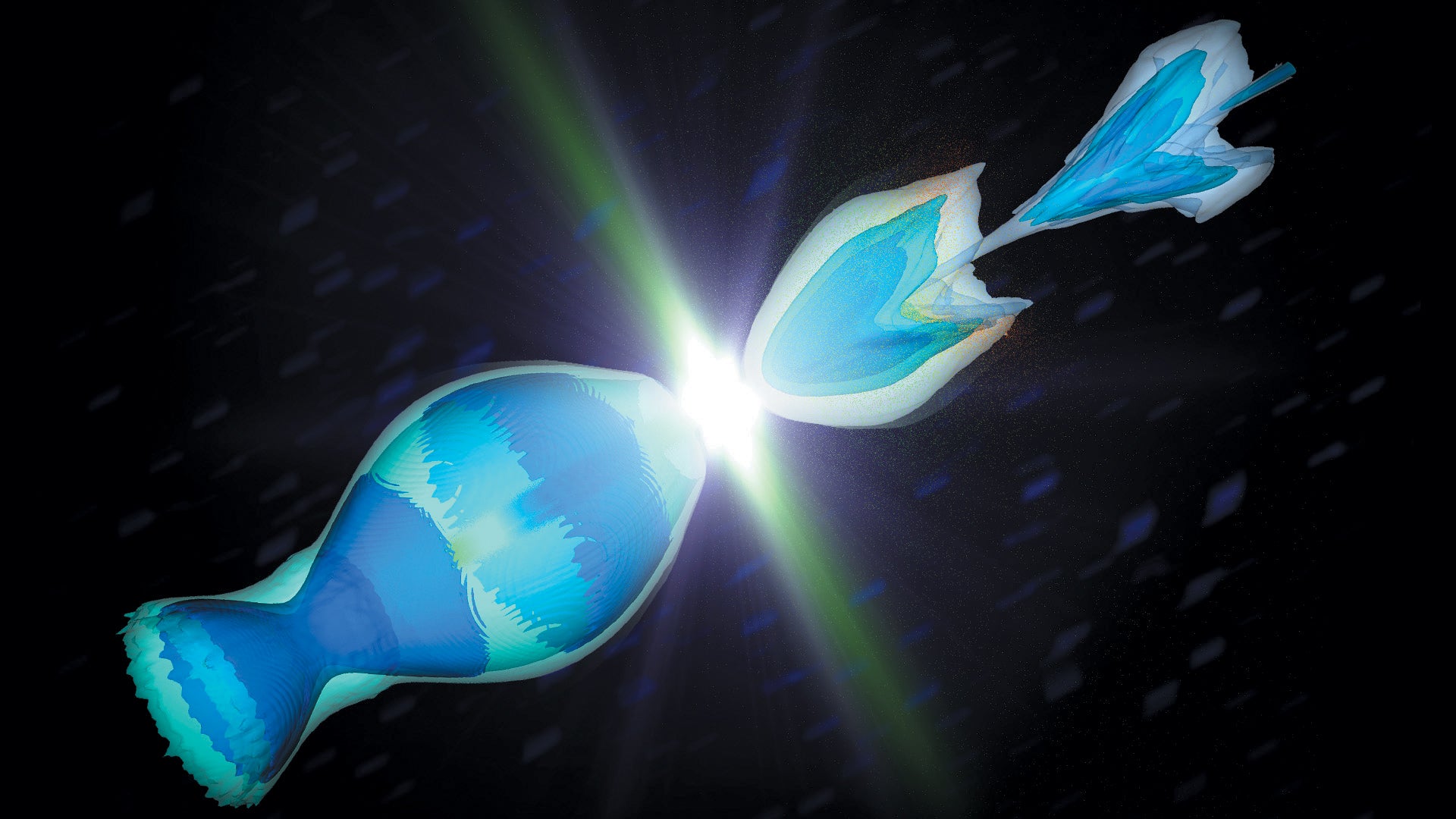

A plasma wakefield accelerator takes advantage of the kind of wake you can find trailing a motorboat or a jet plane. As a boat moves forward, it displaces water, which moves out behind the boat to form a wake. Similarly, a tightly focused but ultraintense laser pulse moving through a plasma at the speed of light can generate a relativistic wake (that is, a wake also propagating nearly at light speed) by exerting radiation pressure and displacing the plasma electrons out of its way. If, instead of a laser pulse, a high-energy, high-current electron bunch is sent through the plasma, the negative charge of these electrons can expel all the plasma electrons, which feel a repulsive force. The heavier plasma ions, which are positively charged, remain stationary. After the pulse passes by, the expelled electrons are attracted back toward the ions by the force between their negative and positive charges. The electrons move so quickly they overshoot the ions and then again feel a backward pull, setting up an oscillating wake. Because of the separation of the plasma electrons from the plasma ions, there is an electric field inside this wake.

If a second “trailing” electron bunch follows the first “drive” pulse, the electrons in this trailing bunch can gain energy from the wake much in the same way an electron bunch is accelerated by the radio-frequency wave in a conventional accelerator. If there are enough electrons in the trailing bunch, they can absorb sufficient energy from the wake so as to dampen the electric field. Now all the electrons in the trailing bunch see a constant accelerating field and gain energy at the same rate, thereby reducing the energy spread of the beam.

The main advantage of a plasma accelerator over other schemes is that electric fields in a plasma wake can easily be 1,000 times stronger than those in traditional radio-frequency cavities. Plus, a very significant fraction of the energy that the driver beam transfers to the wake can be extracted by the trailing bunch. These effects make a plasma wakefield-based collider potentially both more compact and cheaper than conventional colliders.

The Future of Plasma

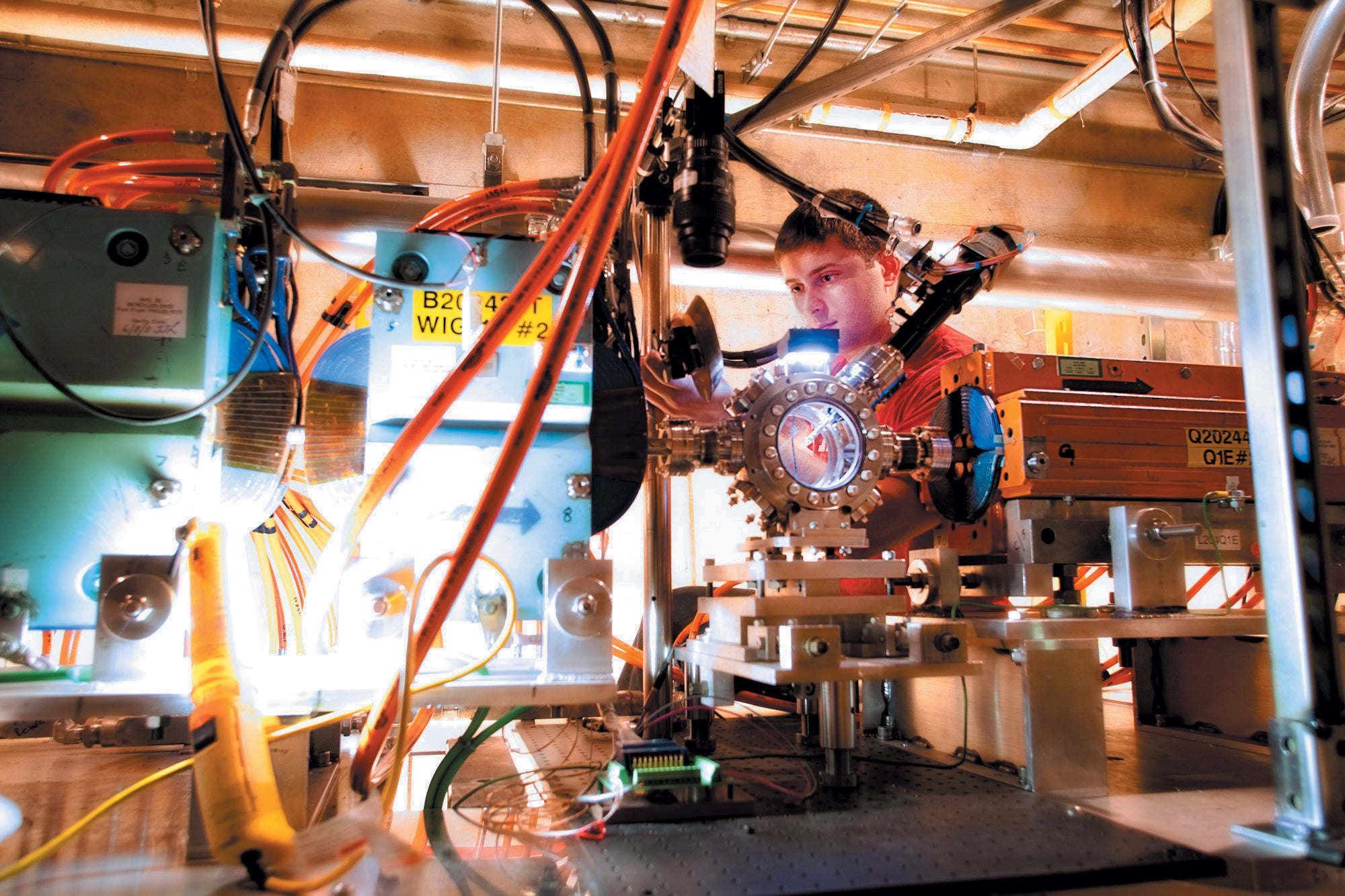

Both laser- and electron-driven plasma wakefield accelerators have made tremendous progress in the past two decades. My own team at U.C.L.A. has carried out prototype experiments with SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory physicists at their Facility for Advanced Accelerator Experimental Tests (FACET) in Menlo Park, Calif. We injected both drive and trailing electron bunches with an initial energy of 20 GeV and found that the trailing electrons gained up to 9 GeV after traveling through a 1.3-meter-long plasma. We also achieved a gain of 4 GeV in a positron bunch using just a one-meter-long plasma in a proof-of-concept experiment. Several other labs around the world have used laser-driven wakes to produce multi-GeV energy gains in electron bunches.

Plasma accelerator scientists’ ultimate goal is to realize a linear accelerator that collides tightly focused electron and positron, or electron and electron, beams with a total energy exceeding 1 TeV. To accomplish this feat, we would likely need to connect around 50 individual plasma accelerator stages in series, with each stage adding an energy of 10 GeV.

Yet aligning and synchronizing the drive and the trailing beams through so many plasma accelerator stages to collide with the desired accuracy presents a huge challenge. The typical radius of the wake is less than one millimeter, and scientists must inject the trailing electron bunch with submicron accuracy. They must synchronize timing between the drive pulse and the trailing beam to less than a hundredth of a trillionth of one second. Any misalignment would lead to a degradation of the beam quality and a loss of energy as well as charge caused by oscillation of the electrons about the plasma wake axis. This loss shows up in the form of hard x-ray emission, known as betatron emission, and places a finite limit on how much energy we can obtain from a plasma accelerator.

Other technical hurdles also stand in the way of immediately turning this idea into a collider. For instance, the primary figure of merit for a particle collider is the luminosity—basically a measure of how many particles you can squeeze through a given space in a given time. The luminosity multiplied by the cross section—or the chances that two particles will collide— tells you how many collisions of a particular kind per second you are likely to observe at a given energy. The desired luminosity for a 1-TeV electron-positron linear collider is 1034 cm–2s–1. Achieving this luminosity would require the colliding beams to have an average power of 20 megawatts each—1010 particles per bunch at a repetition rate of 10 kilohertz and a beam size at the collision point of tens of a billionth of a meter. To illustrate how difficult this is, let us focus on the average power requirement. Even if you could transfer energy from the drive beam to the accelerating beam with 50 percent efficiency, 20 megawatts of power will be left behind in the two thin plasma columns. Ideally we could partially recover this power, but it is far from a straightforward task.

And although scientists have made substantial progress on the technology needed for the electron arm of a plasma-based linear collider, positron acceleration is still in its infancy. A decade of concerted basic science research will most likely be needed to bring positrons to the same point we have reached with electrons. Alternatively, we could collide electrons with electrons or even with protons, where one or both electron arms are based on a plasma wakefield accelerator. Another concept that scientists are exploring at CERN is modulating a many-centimeters-long proton bunch by sending it through a plasma column and using the accompanying plasma wake to accelerate an electron bunch.

The future for plasma-based accelerators is uncertain but exciting. It seems possible that within a decade we could build 10-GeV plasma accelerators on a large tabletop for various scientific and commercial applications using existing laser and electron beam facilities. But this achievement would still put us a long way from realizing a plasma-based linear collider for new physics discoveries. Even though we have made spectacular experimental progress in plasma accelerator research, the beam parameters achieved to date are not yet what we would need for just the electron arm of a future electron-positron collider that operates at the energy frontier. Yet with the prospects for the International Linear Collider and the Future Circular Collider uncertain, our best bet may be to persist with perfecting an exotic technology that offers size and cost savings. Developing plasma technology is a scientific and engineering grand challenge for this century, and it offers researchers wonderful opportunities for taking risks, being creative, solving fascinating problems—and the tantalizing possibility of discovering new fundamental pieces of nature.