Weigh all the creatures that roam the sea, and a striking balance emerges. Researchers have found that the total mass of this life, when grouped in size classes, roughly follows a regular mathematical distribution—although humans may have disrupted part of the pattern.

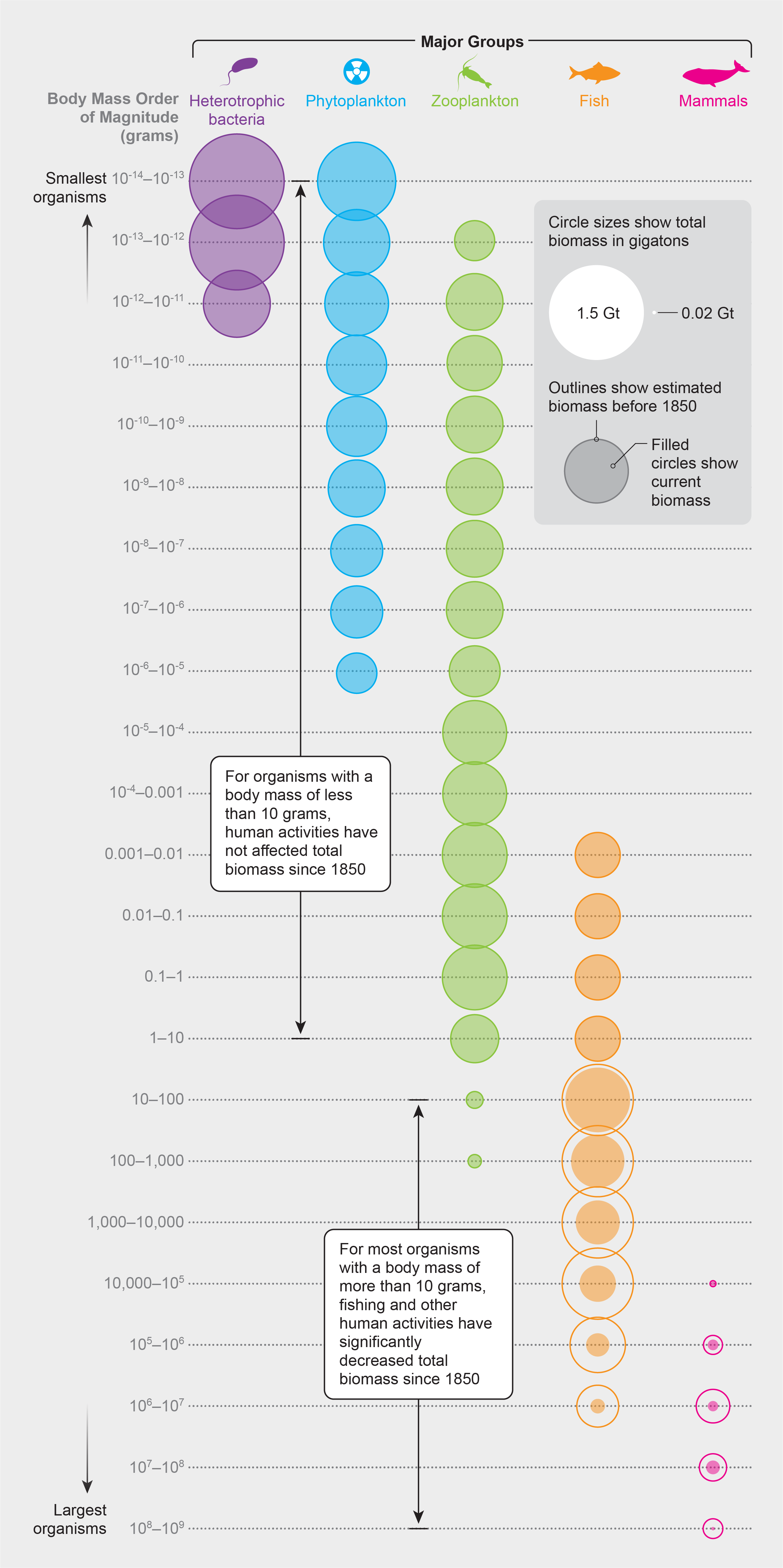

For a study in Science Advances, researchers combined satellite images, water samples, commercial fishing catch data and computer simulations to estimate the combined weight of all the organisms that move through the open ocean. Next they visualized biomass distribution by placing species on a size spectrum segmented into 23 weight classes. To accommodate the vast size differences, the researchers divided classes using a mathematical function called a logarithm: the average weight of organisms in one class differed by a factor of 10 from adjacent classes. One class contained organisms weighing between 0.01 and 0.1 gram, another between 0.1 gram and 1 gram, and so on.

The scientists found that most of the weight classes contain roughly one gigaton of life each. “This could be one of the largest-scale regularities among life on Earth,” says the study’s lead author Ian Hatton, a biologist at the Max Planck Institute for Mathematics in the Sciences in Leipzig, Germany.

Exceptions included a few classes containing bacteria, which were overweight because of microbes’ domination of deep waters, and classes containing animals bigger than 10 grams, which had disproportionately little mass. Wondering if humans had contributed to this divergence, Hatton’s team used previously published computer simulations and animal population estimates to reconstruct the ocean size spectrum of the 1850s, before modern industrial fishing. The researchers found that the combined weight of organisms above 10 grams, including whales and many fishes, has decreased by 60 percent since then.

Overfishing is a well-known problem, but this work helps illuminate its extent, says Andrea Bryndum-Buchholz, a marine ecologist at Memorial University in Newfoundland, who was not involved in the study. “It visualizes how we’ve actually changed the ocean fundamentally,” she says.