NASA astronaut Kayla Barron floated into an International Space Station module in January with a roll of yellow tape and an unusual assignment: setting up the first of six “trenches” for an archaeological investigation.

Back on Earth, archaeologists Alice Gorman of Flinders University in Australia and Justin Walsh of Chapman University in California watched and offered feedback. They had previously mined existing video footage to study astronaut culture, but their Sampling Quadrangle Assemblages Research Experiment, dubbed SQuARE, marks the first real off-world “dig.”

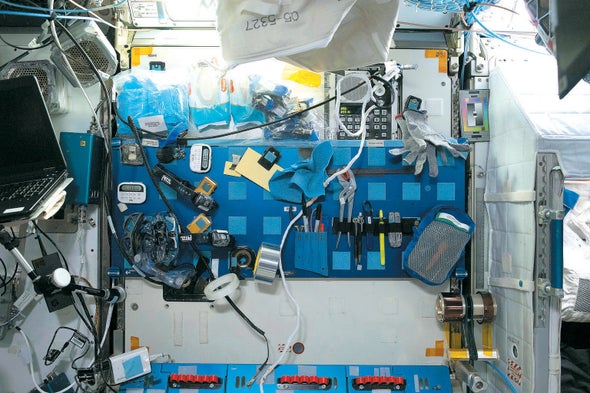

In terrestrial archaeology, researchers often record every bone, pottery fragment and stone tool found in small, well-defined trenches. Adapting that well-honed methodology, SQuARE had astronauts take daily photographs of one-meter squares marked off by tape. The researchers back on Earth then documented all objects entering and exiting those six spots over 60 days, until the work wrapped up in March. “Every image is like a layer of soil that we’re removing, revealing a new period and a new set of activities that have happened in that area,” Walsh says. The sampled areas included a workstation, a galley and the wall across from the U.S. toilet. These trenches were full of artifacts, including scissors, wrenches, pens, condiments and one of Gorman’s obsessions: Ziploc bags.

“Lots of people think of archaeology as gold masks and pyramids and sculptures and things like that,” Gorman says—not the utensils, pots and other objects more often studied. “That’s the really fascinating stuff.” Amid the expensive, highly designed and irreplaceable components often found in spacecraft, mass-produced plastic bags affixed to surfaces are crucial as a form of what Gorman calls “portable gravity,” along with Velcro, cable ties, handholds and footholds that help items (and people) stay in place.

Better data on such artifacts’ use could influence future space habitat design. And SQuARE has a historic preservation component, too: the more than 20-year-old station is set to be decommissioned in 2030. “It’s really the direction that space archaeology should go,” says anthropologist Beth O’Leary, a pioneer in this burgeoning field and professor emerita at New Mexico State University, who was not involved in the study. SQuARE data could illuminate how astronauts create subcultures in space, she adds.

In earlier work, the team showed how Russian cosmonauts over several decades and multiple space stations informally passed down a way of using empty wall space to create shrines honoring heroes such as astronaut Yuri Gagarin. “There seems to have been a transmission of what to do,” Walsh says, “which is what culture is—it’s these traditional practices that get developed, then reinforced and transformed.”