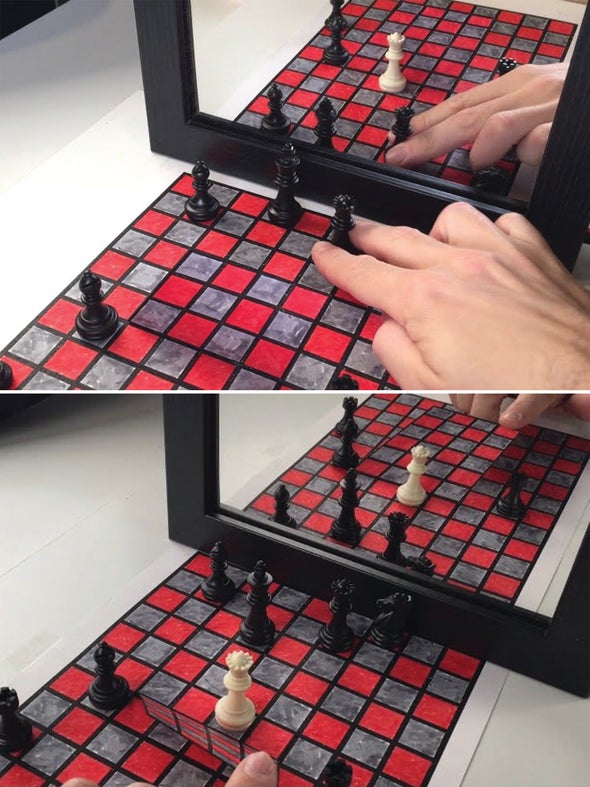

Black chess pieces move across a hand-drawn red-and-gray chessboard. A black-framed mirror, placed in front of the board, reflects the progress of rooks and bishops across the space. Except that something is not quite right. The white queen, standing at the center of the board, exists only in the mirror reflection. In the foreground, the physical board’s central squares appear incongruously empty. The Phantom Queen Illusion, conceived by U.K. magician Matt Pritchard, astonished worldwide viewers last December, winning first prize in the 2021 Best Illusion of the Year Contest.

Although Pritchard’s queen appears simultaneously present and absent, this is neither a quantum paradox nor image manipulation. The answer lies in Pritchard’s clever use of anamorphic camouflage, combined with dual—and seemingly incompatible—perspectives. Anamorphic perspective is a type of distorted projection that relies on the viewer assuming a specific vantage point. In Pritchard’s illusion, the critical component is a camouflaged “invisibility cloak,” whose shape and pattern shield the queen from not just one but two viewing angles: the viewer’s vantage point and the mirror’s reflection.

Pritchard devised the deception after reading a book of photography tricks by Walter Wick. “One picture featured an ‘invisible cube’ that was painted to blend in with the background,” he recalls. “The magician within me started to wonder how I could exploit an invisible object in a scene. I decided to use it as an [undetectable] shield to hide an extra object before making it appear.”

Next, Pritchard asked himself if he could make a shield that would work from two angles. “After many dozens of attempts, I managed to design a shape and pattern that could work from both sides.. . . Since I was using a checker pattern, a chessboard-themed illusion was a natural choice.” To complete the effect, Pritchard optimized the lighting to remove any telltale shadows from the image.

The last factor in the deceit was the viewer’s own mind and its faulty assumptions. “We’ve become accustomed to looking at a reflection and seeing a reversed image of a scene,” Prichard says. “It’s disarming to find a major discrepancy between the real and the virtual images.”